Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality in the UK, with 1,000 new cases each day and half of the population born after 1960 expected to be diagnosed with the disease during their lifetime. Although data indicates that UK cancer survival rates are improving, the country still lags behind other comparable countries. There are many, complex reasons that could explain this trend. It is clear, however, that much progress still needs to be made in the UK in relation to timely diagnosis and swift access to treatment, both of which are essential in delivering better health outcomes and increased survival rates.

Cancer waiting times are a key performance measure and the access standards are set out in the NHS constitution. Since their introduction in 2009, the waiting times targets were initially met on a consistent basis in England. But over the past two years performance has deteriorated and data for 2019/20 to date indicates that performance has now reached an all time low since the standards were introduced.

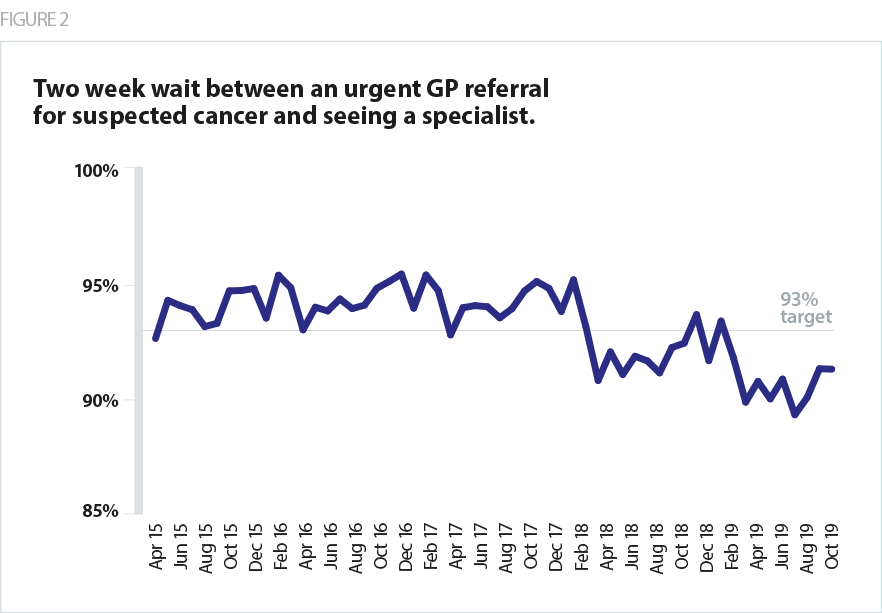

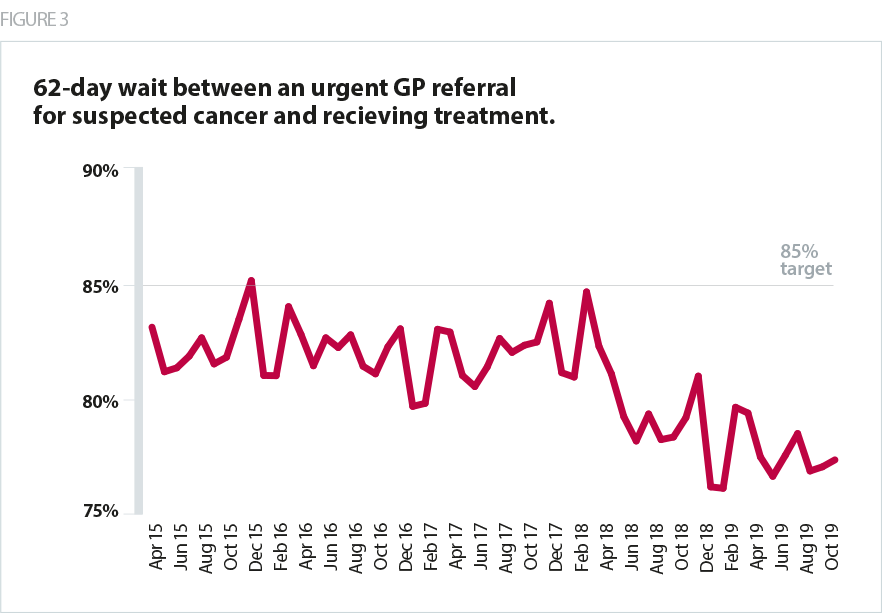

The latest data for November 2019 saw performance against the two week urgent referral standard (GP referral to consultant appointment) some way below the 93% target, and this has now been missed for 18 of the past 20 months. The 31-day standard (decision to treat to a first treatment) was also below target in the latest figures, and while this was previously thought of as a given, it has now been missed five times this year. The third of the three headline standards (62 days from GP urgent referral to first treatment) has also consistently been missed, in this case having not been met since December 2015, and performance currently sits eight percentage points below the 85% target.

Demand for cancer services has never been higher, mirroring the pressures experienced across the whole of the NHS. This blog, updated with the latest figures available in January 2020, outlines the current performance trends against the cancer targets and quality indicators, as well as discussing the key priorities for improving outcomes for cancer patients within the wider health landscape.

The current cancer waiting time targets

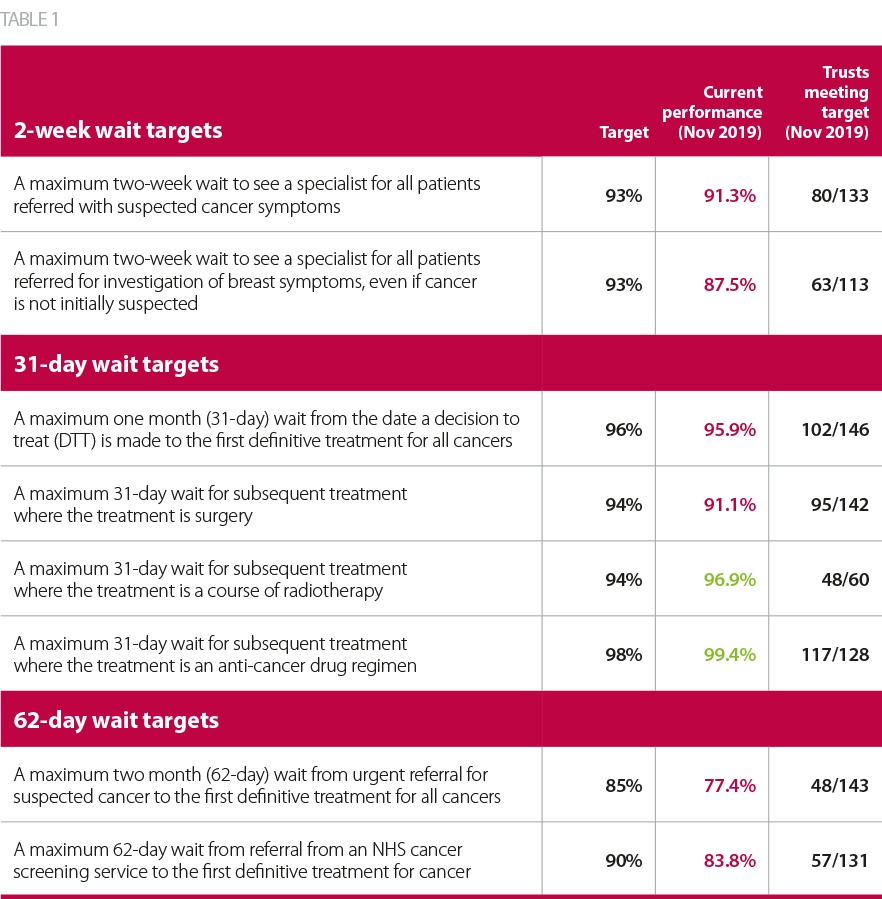

There are currently eight operational standards for cancer waiting times and three key timeframes in which patients should be seen or treated as part of their cancer pathway; two weeks, one month (31 days) and two months (62 days). Following the recommendations from the Independent Cancer Taskforce in 2015, NHS England will also be introducing a new 28-day diagnosis standard from April 2020 as part of the focus on improving early diagnosis and treatment. The ongoing clinical review of standards being carried out by NHS England is underpinned by an ambition to reflect modern clinical practice and increasing personalisation of treatment. Subject to the final recommendations of the review team, the revised standards, including a new suite of metrics for cancer services, may be rolled out to trusts over the year ahead.

NHS performance against each standard in November 2019 is listed alongside each target in table one below, as well as the number of trusts meeting the target.

Recent trends in cancer target performance and quality indicators

Effect of rising demand on waiting times

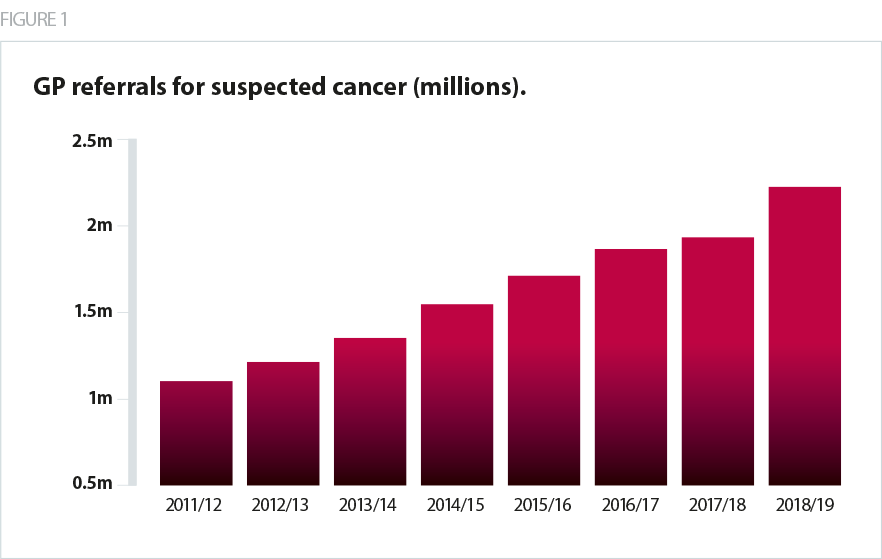

Demand for cancer services has increased year-on-year, with 2018/19 seeing over 2.2 million patients referred by their GP for suspected cancer, more than double the number in 2011/12. A number of factors are driving this increase, including the changing age profile of the population, increased awareness of the disease and prompts to take early action highlighted in national campaigns, as well as changing medical practice, guidelines and referral thresholds.

As the number of people being referred by a GP has risen, a larger proportion are now having to wait longer than two weeks to see a specialist. For a time, it appeared that the service was able to accommodate the rising demand with only a slight drop in performance against this standard between 2011-2017. However, since April 2018 this target has been missed nearly every month, and a tipping point may well have been reached where key shortages in workforce and equipment are resulting in performance not keeping pace with demand.

Another area of high concern is the 62-day standard, which has been consistently missed at a national level since 2013/14. In the most recent figures, national performance was 77.4%, with only a third of trusts able to meet the 85% target. This means that more than one in five cancer patients are now waiting longer than 62 days to start treatment following an urgent GP referral. This target is the only current waiting time standard which takes into account the patient’s entire pathway from a referral to treatment, which may explain why performance has been worse relative to some of the other cancer standards. Proposals to introduce new standards for cancer services that provide further insight into time to diagnosis within the pathway will be out for consultation in 2020.

Delays in any area of care have an impact on patients. But in cancer care, the amount of time a patient waits for diagnosis and treatment can significantly affect outcomes and experience. The data suggests that the increased number of referrals is placing additional strain on cancer services, and while the system has responded by seeing more people within the standard, the proportion being seen within target is falling as demand outstrips the resources available. These pressures are also evident across other NHS performance measures including the elective care waiting list, in emergency departments, and in mental health, ambulance and community services, signifying the challenges the NHS is facing in meeting current levels of demand across the board.

Sustaining the focus on high-quality care

Although performance has slipped against the cancer targets, there are some positives to note which emphasise the exceptional care that trusts continue to provide to cancer patients. The NHS has been working to streamline diagnosis for people with suspected cancer, using rapid diagnostic centres rolled out under the NHS long term plan following pilots in various parts of the country.

New screening tests are also being promoted: a new bowel cancer test making it easier for over four million people to use; primary HPV testing is being introduced which will see three million women tested each year; and targeted lung heath tests are being offered in mobile locations around the country in a drive to catch conditions earlier. The recently concluded independent review of adult screening programmes makes a number of recommendations around improved governance and effectiveness. In another positive step, since September 2019 the HPV vaccine is now being offered to boys as well as girls, with many thousands set to benefit. Continuing to develop and deliver these methods will be essential as the NHS long term plan includes a goal of saving an extra 55,000 lives each year within a decade by catching three quarters of all cancers early.

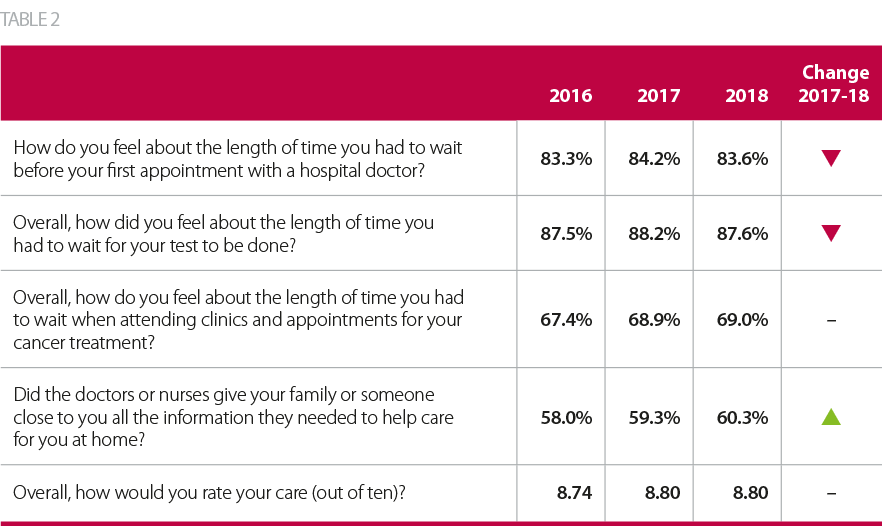

The results of the 2018 national cancer patient experience survey provide further evidence of the increasing challenges in delivering services for cancer patients. On a positive note, patients gave the same overall rating of their care in 2018 as they did in the 2017 survey (8.8 out of 10), and higher than the 2016 survey (8.74). Additionally, several questions on the provision of information saw improved responses from the previous year, indicating some progress in aspects of communication. However, responses for many of the questions regarding access to care deteriorated, and this is likely to remain a challenge as demands on staff and resources increase. Responses to select questions from the survey are outlined below in table two.

What next for NHS cancer services?

The demand figures and performance data clearly illustrate the immense strain on trusts to deliver high quality cancer services. The government’s recent election manifesto commits to increase capital funding and proposes steps to grow the NHS workforce, which both are positive for cancer services. It is also encouraging to see that patient satisfaction remains broadly high. However, this will be increasingly difficult to maintain as operational pressures rise across the whole of the NHS.

Two issues stand as major hurdles to overcome: workforce shortages and lack of capital investment.

Some progress has been made against the cancer workforce plan (part of the Five year forward view). An initial report published earlier this year identified increases in a number of staff groups, alongside the creation of new routes into the cancer workforce. However, we continue to hear from trust leaders about worsening shortages of cancer nurse specialists who are able to administer chemotherapy, certain specialist oncologists, as well as huge gaps in the diagnostic workforce including radiographers and endoscopists. Making matters worse is the ongoing NHS pensions crisis, which is seeing consultants and other senior staff reducing their hours, undertaking fewer waiting list initiatives and in some cases taking early retirement to avoid large unexpected pension tax bills.

Equipment and facilities are another key consideration, as recognised by the recent announcement of an extra £200m for new scanners and diagnostic equipment across 78 trusts. While encouraging, this needs to be viewed in the wider context of the current NHS capital regime. There is a lack of efficient and effective mechanisms for prioritising, accessing and spending NHS capital based on need. Our Rebuild the NHS campaign calls for a multiyear capital funding settlement and improved processes. This is particularly relevant for trusts providing cancer services that need the best technology and facilities to deliver world leading services.

The ambitions in the long term plan and the ongoing clinical review of standards are commendable but certain areas need specific attention to enable trusts to deliver essential improvements in cancer services. These include sufficient and effective funding, the right workforce, adequate screening for early diagnosis and the right technology. All must be prioritised to provide services that are fit to cope with the needs of a population where one in two people will get cancer in their lifetime.