There is a large amount of variation in the approaches trusts are taking to address health inequalities, as action is needed across a range of different activities and areas, and the priorities for each trust will be dependent on the needs of its population. Identifying priorities is important for trusts to focus their attention on areas where they are likely to have a bigger impact in addressing inequalities within their local communities.

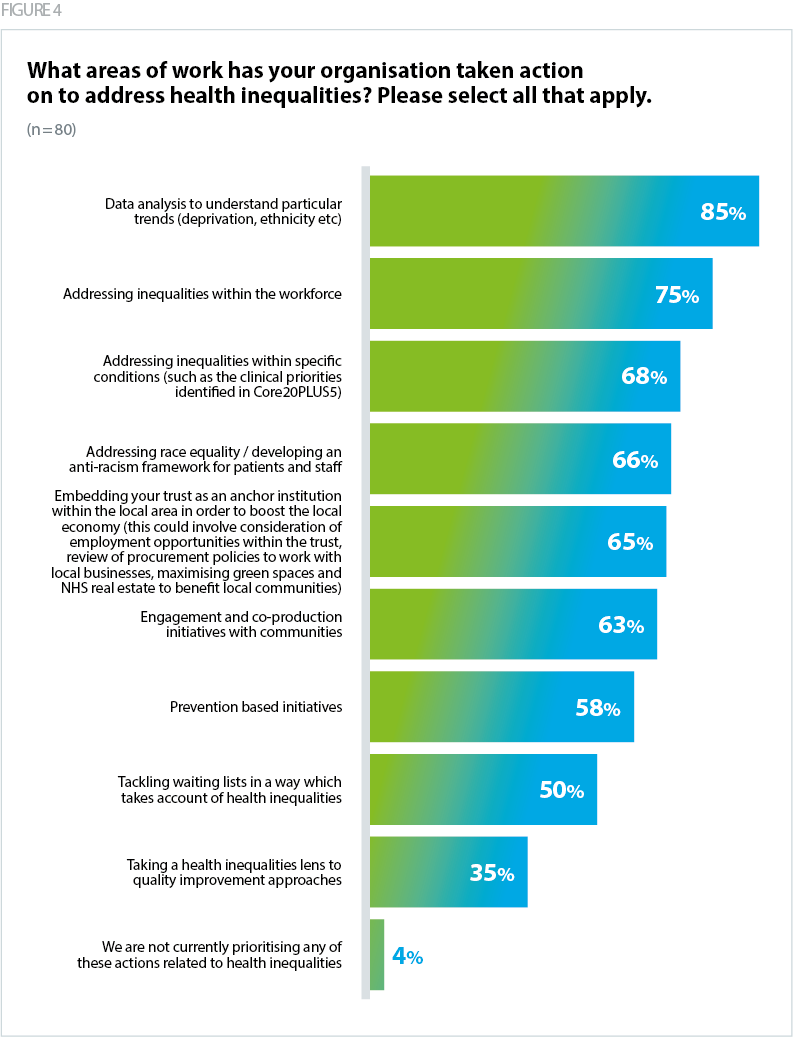

Our survey asked respondents to identify the main areas of work their organisation has chosen to address health inequalities. The results show relatively high responses to each of the options – indicating the range and spread of activity in this area. The most common approach within trusts was 'data analysis to understand particular trends' (85%). Understanding data trends underpins much of the other activity, as it can highlight where trusts need to prioritise effort and action. 'Addressing inequalities within the workforce' (75%) and 'addressing inequalities within specific conditions' (68%) were also common areas of focus.

"Sometimes there is a need to remind ourselves of the key priorities rather drowning in a very broad range of smaller initiatives"

Fewer respondents selected 'taking a health inequalities lens to quality improvement (QI) approaches' (35%) – suggesting that this approach is potentially not well embedded among trusts. This is perhaps reflective of the relatively new creation of NHS Impact, which represents the NHS’s shared improvement approach, which may not yet be well understood across all trusts.

Inclusive recovery of NHS services was identified as one of the five strategic priorities for tackling health inequalities in the 2021/22 NHSE operational planning guidance. Systems were asked to identify inequalities in NHS performance by ethnicity and deprivation and to prioritise service delivery by taking these factors into account (NHS England, 2021c). Over time, however, national focus on inclusive recovery has declined, and while the latest 2023/24 planning guidance reiterates the call to deliver against the five priorities, it does not explicitly mention inclusive recovery or outline a specific objective on it (NHS England, 2024). Instead, the focus on elective recovery is on eliminating 65-week waits by September 2024, reducing the overall list size and improving productivity. It is therefore unsurprising that only half of respondents (50%) indicated that their trust is focusing on 'tackling waiting lists in a way which takes account of health inequalities'. Executive leads tell us that where this work is taking place, it is being targeted at specific services rather than taking a whole-organisation approach. Some trusts have also been reviewing cancellation and Did Not Attend (DNA) rates by deprivation and ethnicity to target interventions in reducing waiting lists.

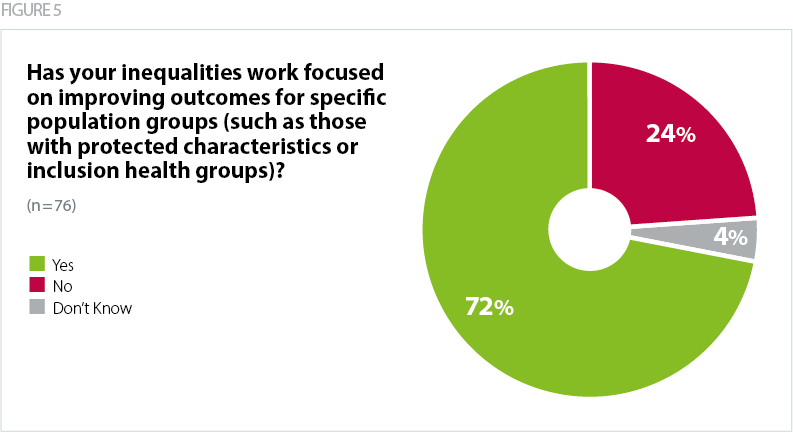

A key component of NHSE’s Core20PLUS5 framework for reducing health inequalities is identifying 'PLUS' groups that require targeted support and interventions (NHS England, 2021b). Our survey results found that nearly three quarters of respondents (72%) are prioritising their health inequalities work on improving outcomes for specific population groups. Over half of respondents said that they had prioritised by ethnic group. Other population groups that trusts are prioritising included homeless populations, asylum seekers and migrants, prisoners, LGBTQ+ communities and children and young people. Trusts are encouraged to understand their local need, through data analysis and interpretation, considering the full range of protected characteristics and inclusion health groups (NHS England, 2023c).

"Non-White ethnicity groups - disparities are evident across all of our services, and there is a significant intersection with deprivation."

"People experiencing homelessness. Homelessness is a health and social care problem … homeless patients attend A&E six times as often as housed people. They are admitted to hospital four times as often and stay twice as long. Numbers of people experiencing homelessness are rapidly increasing, and the number receiving enhanced primary care has increased by 90% over the past four years, from circa 720 to 1300."

Trusts identified that being selected as a pilot site for specific policies or guidance implementation successfully enabled the trust to dedicate attention and resource to the agenda. For example, one trust was piloting the Equality Delivery System and had developed a comprehensive action plan around this.

Employing public health consultants has supported some trusts to excel in the operational delivery of their health inequalities work. Healthcare public health professionals (both registrars and consultants) were recognised as having the right knowledge, expertise and skill set (especially in data analysis and interpretation). Whether trusts employed a public health workforce or not seems to separate out trusts that are developed or underdeveloped in the health inequalities space. Trusts with access to public health expertise stated the clear benefits of this staff group – one trust recommended that their main advice around health inequalities was to "invest in public health". However, employing public health colleagues is not widespread across all trusts. Some trusts we spoke to were looking to build their public health capacity but noted a lack of funding to resource public health consultants. There was little awareness of how trusts could offer training placements for public health registrars. Trusts are encouraged to work with public health colleagues in local authorities.

"We have developed a public health consultant JD, which got the necessary approval last week. We are due to go out to recruitment. The plan is that this post holder will be key to moving this agenda forward in a considered and evidence based way."

The scope and breadth of health inequalities work can in and of itself present a challenge for trusts in prioritising specific areas of work and determining a strategic direction of travel. While the 2024/25 planning guidance requires ICBs to publish joined up action plans to address health inequalities and implement the Core20PLUS5 approach (NHS England, 2024), publication of a national strategy on health inequalities, with a specific set of priorities, could meaningfully drive collective action, whilst also providing flexibility for trusts to respond to local need. A strategy would give trusts clarity on a core set of asks, that could be used to benchmark progress and guide accountability structures. We understand that NHSE is intending to publish a national health inequalities strategy later this year.