This is the second year running that we have asked for trust's views regarding the oversight and regulation of systems.

The NHS long term plan confirmed system working as the key driver of change within the sector with multiple expectations of STPs and ICSs forming to maximise the use of collective resource in a local system, and to improve, and integrate care. The long term plan also set out that regulatory frameworks will be realigned to support system working, with providers being held accountable to system wide objectives and goals, in addition to existing organisation-level accountabilities.

The plan states that:

- NHS England and NHS Improvement will work more closely with other regulatory bodies to set clear and consistent system-wide expectations and commit to keeping assurance and oversight proportionate.

- ICSs will agree system-wide objectives with the relevant NHS England and NHS Improvement regional directors, who have responsibility for oversight of health care in their regions, and be accountable for their performance against these objectives. ICSs will then have the opportunity to earn greater authority as they develop and perform.

- A new ICS accountability and performance framework will consolidate existing accountability arrangements and will provide a consistent and comparable set of performance measures, including the new 'integration index'.

- CQC intends to place greater emphasis on system-wide quality in its regulatory activity so that providers are held to account for their activity to improve quality across a local area.

Despite this shift in the operating environment, no changes have been made to the legislative framework underpinning the NHS. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), trusts boards and local authorities remain responsible and accountable for the commissioning and provision of services, underpinned by the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Crucially, STPs and ICSs have no legal status and derive their legitimacy from the statutory bodies which comprise them.

In terms of regulation and oversight of the provider sector as it stands, the 2012 Act aligned national bodies' responsibilities and regulatory frameworks to sectors and institutions. This has translated over time into NHS Improvement monitoring and assuring the performance of NHS trusts and foundation trusts through the single oversight framework (SOF), and NHS England carrying out a parallel assurance role for CCGs using the CCG improvement and assessment framework (IAF). However, in August 2019 NHS England and NHS Improvement published the new NHS oversight framework which brings together the previously separate approaches to provider and commissioner oversight, and reflects the priority of system working as set out in the long term plan. This new framework has superseded the SOF and the IAF.

All of the above serves to highlight that providers, their local partners, and the national bodies are continuing to navigate a complex environment, and developing new regulatory models to reflect the changes taking place locally will only grow as a priority.

New models of system oversight

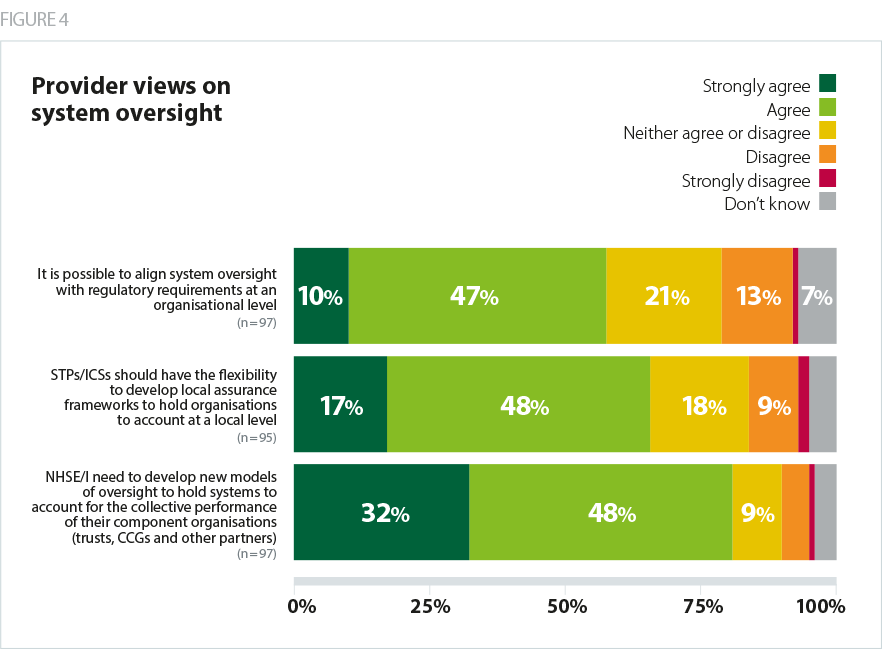

As we saw last year, a significant majority (80%) of trusts continue to agree that NHS England and NHS Improvement need to develop new models of oversight to hold systems to account for the collective performance of their component organisations, as shown in figure 4.

If we are to move towards greater systems working, then regulatory oversight at systems level is essential.

When asked about the ways in which the existing regulatory framework discourages the development of effective system working and what changes could be made to the framework to stop this from happening, multiple respondents highlighted the conflict between regulatory frameworks focused on individual organisations and the drive towards greater collaboration and system working as a key issue, and commented on the need for clear and robust approach to regulation and monitoring at a system level. A number of trusts said setting individual control total has had a particularly negative impact on system working.

Still holds individual organisations to account without any view on the role played in the system - appreciate that this is due to the legal framework we currently operate in.

There is confused thinking over the role of STPs and ICSs in relation to oversight. NHS England and NHS Improvement appear to be looking to delegate oversight of local systems to STPs. However, (1) STPs are not statutory bodies (2) they are not resourced to manage performance (3) providers are members of STPs and indeed some are chaired by provider chief executives.

Financial control total approach encourages providers and commissioners to be in a transactional and adversarial relationship.

Oversight at a system level will impact individual organisational regulation. As a consequence of contributing to a system-level plan, which commits to deliver services differently for the local population, some individual organisations may be disadvantaged or advantaged. The potential risks and gains need to be shared appropriately across organisations and monitored at a system level. Trusts facing performance issues will, in particular, need flexibility from the regulators to balance system responsibilities with requirements to improve organisational finance and performance (NHS Providers, 2019).

Despite continued support for new models of oversight at a system level, numerous respondents highlighted the complexity in trying to take a collaborative approach in a legislative framework set up for competition. At the moment, any regulatory intervention or enforcement action can only be taken at individual organisation level, as STPs and ICSs are not statutory bodies. In addition, while the regulatory framework needs to adapt as system working develops further, it is important to bear in mind that there is a great deal of variability between local areas on their journey to becoming an ICS. There therefore needs to be flexibility in the application of regulation and oversight during any transition from national bodies regulating individual organisations to whole systems.

The variation in the maturity of local systems appears to be reflected in our findings around trusts' views on STPs/ICSs having the flexibility to develop local assurance frameworks to hold organisations to account at a local level. Nearly two thirds (65%) of trusts agreed they should have this flexibility, which is a similar proportion of respondents who agreed with this statement last year (61%). It is possible that those in agreement are part of more established and developed local partnerships, which could benefit from negotiating additional freedoms and flexibilities with the national bodies. In these cases, careful consideration needs to be taken by NHS England and NHS Improvement on which elements of oversight must remain at a national level, and which can be transferred to the regions or to local systems.

Trust leaders who disagreed that STPs/ICS should have such flexibility commented on local systems lacking the infrastructure and resources required to take on an assurance role and manage performance, which was a theme that emerged from last year's survey. Similarly to last year, some trusts also continued to express concern around the potential for conflicts of interest to arise if STPs/ICSs, which derive their decision making powers from the statutory bodies which comprise them, are holding those very organisations to account.

No "place based" accountability process or forum.

Just not well enough developed yet.

Local leadership is lacking.

Aligning system oversight and the regulation of organisations

As we stressed in last year's report, it is crucial that oversight and assurance frameworks respond as local systems evolve to ensure that the oversight of systems does not simply create an additional layer of performance management, with no added value, or create multiple conflicting judgements or ‘double jeopardy’. Ideally, any additional regulatory requirements at system level require a commensurate reduction in the existing regulation on individual organisations.

Over half (58%) of trusts who responded to our survey agreed it is possible to align system oversight with regulatory requirements at an organisational level. Achieving the required alignment still feels far off - numerous respondents highlighted that the regulatory bodies not coordinating their work as a key issue, which is increasing the burden of regulation on them as a result. Furthermore, only 20% of trusts agreed the regulators take the context of local system working adequately into account in their judgements of individual providers, with 51% disagreeing. A number of trusts commented that CQC and NHS Improvement could better reflect the context within which a trust is working in their assessments and reports.

If CQC were to develop a methodology to inspect systems we would be able to transform our services with greater pace.

CQC do not appear to take into account commissioning decisions and the scale of commissioning investment (or not) and its impact on the service delivered.

Huge burden of regulation not all pointing in the same direction.

More so than ever, trusts are feeling the tension between the current institutionally-focused regulatory model and policy ambitions to develop methods of oversight for local systems. Trusts feel that the move to greater system working and system-level oversight offers opportunities to promote and support collaboration across health and care, but also risks blurring well established lines of accountability, and placing additional regulatory burden on providers as they face organisational regulation and the development of a new system oversight framework.

Successful development of collective responsibility will depend in part on the relationships developed between trusts, CCGs, STP/ICS leaders and the new regional directors. It is essential that there are clear lines of responsibility, accountability and decision making.