Operationally, the health and care sector, entered last winter in a more difficult position than ever before. Despite the welcome funding increase announced for the NHS’ 70th birthday to underpin the long term plan, additional funds did not come on stream until 2019/20. Looking ahead, independent experts still say the funding settlement falls short of what is required to recover performance and transform services to meet future needs, following the longest and deepest financial squeeze in the history of the NHS.

But the real story of winter highlights how the NHS adapts to the challenges it faces and how - with preparation, resilience and by adopting learning – the health service can find innovative ways to maintain the high standards of quality we all expect. Below we summarise the vital lessons that can be taken from 2018/19 based on feedback from our membership:

1) The importance of preparation

This winter showed just how useful preparation can be in supporting providers to maintain performance. This year there was a specific focus on reducing length of stay, improving patient flow, increasing the use of ambulatory care units, and trying new staffing models. Trusts across England also made every effort to ensure all staff were offered the flu vaccination. The preparation resulted in a number of successes over the winter months.

Up until Christmas the sector was performing well. A&E performance remained stable and there was less anxiety about operational risk in the run up to winter compared to the previous year. Although the conditions changed in the New Year, the story underneath the figures shows that the preparations trusts made really did help them cope and better accommodate the extra demand. Among trusts’ achievements were:

- A 12% reduction in the number of patients waiting 21 days or more and a 7% reduction in the numbers waiting more than seven days. Providers rolled out a range of initiatives such as green/red days, setting up ambulatory care units, implementing the SAFER patient flow bundle and expanding assisted discharge services.

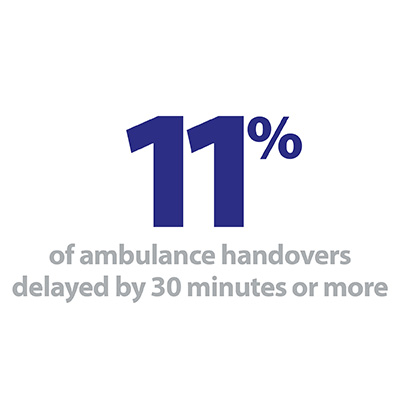

- Shorter ambulance handover delays. Despite the ambulance service having the highest activity levels ever, there were fewer handover delays than last year. This meant that ambulances could get back into the community where they were needed more quickly. And ambulance trusts have been working more collaboratively with providers in their patch to better manage demand across multiple systems.

- A 27% reduction in the number of people waiting longer than 12 hours from the decision to admit to admission. There were 1,416 people who waited longer than 12 hours – which works out as 10 patients per one of the 134 trusts with an emergency A&E department.

- Additional capacity created by local innovation which also helped meet some of the extra demand and saw fewer escalation beds open than last year.

2) The commitment and compassion of NHS staff

Yet again staff pulled out all the stops to deliver the best care possible for their patients during a very challenging start to the year. Although performance against key standards fell, NHS staff responded by; taking more people to hospital by ambulance than ever before; seeing an additional 240,000 patients within four hours in A&E; carrying out an additional 332,000 diagnostic tests over the three months; and reducing the number of patients waiting over 52 weeks for elective care each month.

But we must not take for granted this high level of commitment and service from staff. Given the year round pressures the NHS now experiences, staff wellbeing is beginning to suffer with increased risk of burnout and increasing sickness absence.

Although frontline staff display extraordinary resilience and dedication, workforce shortages make current working conditions more difficult with trusts increasingly having to move staff around to ensure they are providing safe care across services. The NHS interim people plan is a step in the right direction in terms of increasing future supply of staff, but with public satisfaction with the NHS at its lowest level in more than a decade, continued staffing shortages understandably impact on morale.

3) National bodies and trusts must share what is working well and learn when things work less well.

There are three systemic issues which national bodies and trusts can learn from when thinking about how we prepare for future winters.

Firstly, building local relationships and system working is instrumental to finding creative solutions to the problems that the NHS and the care sector are experiencing. Better collaboration between the NHS and local authorities, between physical and mental health services and between primary and secondary care are unlocking new initiatives that are better for patients.

Many of our members shared examples of how these relationships are developing locally to support improvements including; partners in Sussex having a co-ordinated response in trying to reduce out of area mental health placements; collaboration in Dorset aimed at reducing readmission rates of older people; and the Red Cross working with trusts to support quicker discharges, helping with hospital transport or reducing frequent A&E attenders – highlighting the valuable role the third sector can play.

Secondly, central bodies must allocate any additional winter funding as early in the financial year as possible. Over the last few years there have been capital investment announcements later and later, and this year trusts were asked to apply for funding for winter projects they had to be able to complete by 31 December 2018. The quick turn around means that trusts are not able to factor in this additional resource to their preparations, creating missed opportunities which also drive poor value for money as trusts need to spend the money within tight timeframes. The national bodies must also be more open and transparent when it comes to the process for allocating additional funds as communication was muddled with some trusts not eligible for additional help.

Lastly, we must acknowledge that demand for the NHS is going to keep increasing and manage the expectation of what trusts can be asked to deliver so they have a realistic task. Early evaluations of some of the new care models suggest that they are uncovering more unmet needs and increasing the pressure on acute services – the very thing it was hoped they would begin to reduce. Furthermore, the expansion of mental health provision along with a multitude of other factors is continually uncovering more demand for mental health services.

Our members told us that this winter it wasn’t just the high volumes of people they were seeing, but also the severity of their illnesses which was striking. Therefore this isn’t necessarily just a matter of redirecting patients to other services or a public education campaign – although these things are also important. We must acknowledge that this increase in patient acuity and dependency puts even more pressure on staff and is reflected in the evolution of clinical practice over the last 20 to30 years.

Now, with a funding settlement in place, together with more than 300 new commitments set out in the long term plan, there is a real risk of expectations running still further ahead of what the NHS can realistically deliver.