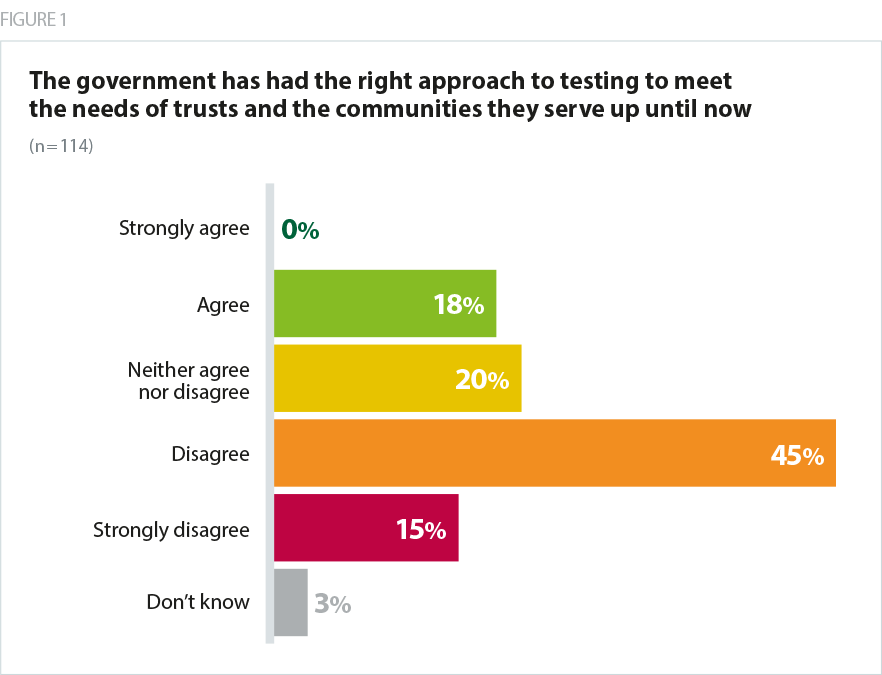

From the outset of the pandemic, the government’s testing strategy has failed to inspire confidence among trust leaders. This view is clearly reflected in the survey findings, with only 18% of respondents agreeing that the government has had the right approach to testing to meet the needs of trusts and the communities they serve. Six in ten either disagreed (45%) or strongly disagreed (15%) that the government has taken the right approach.

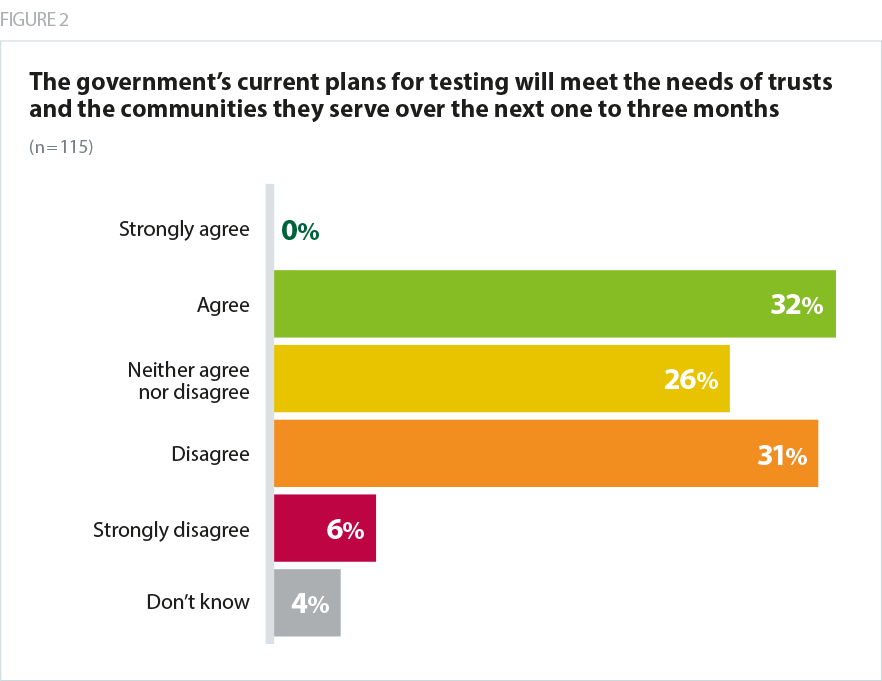

Our survey deliberately asked trust leaders for their views on the national testing strategy in two separate contexts. Firstly, we asked whether they were happy with the overall national strategy since the outbreak. Secondly, we questioned whether trust leaders support the current approach, to reflect a sense we’ve been given from some trusts that some improvements have been made in recent weeks. This was particularly the case following the appointment of the current national leadership group within the testing programme in May, alongside the eventual launch of test and trace.

However, even this positive impression has been accompanied by a wider sense of concern over a lack of coherence in approach. The feeling that there has been no single clear and consistent national strategy for testing is supported by the experience of three seemingly distinct phases. First with multiple national bodies and senior figures contributing in response to the outbreak in March, second under the guidance of Professor Newton and third under the leadership of Baroness Harding, accompanied by the introduction of test and trace. If recent reports (Health Service Journal, July 2020) about a further change in leadership are to prove accurate, the national testing programme could soon enter a fourth phase of direction.

The government’s inability to ensure a clear strategy from the outset, or to effectively overcome the inevitable challenges that have arisen since then, is still affecting confidence in the national plan. While the proportion of trust leaders who agree with the current approach to meet testing needs in the next one to three months is higher (32%), a greater proportion still disagree or strongly disagree (37% combined) that the government’s current plans for testing are adequate.

A range of reasons were cited by respondents for their lack of confidence in the government’s approach, with recurring themes around a focus on meeting targets or numbers “rather than quality or impact”:

- the need for wider testing and community contact tracing earlier in the pandemic

- a lack of clarity in messaging and about who is responsible for what

- a persistently slow turnaround times for testing.

We just don’t know what the plans are or what is being asked of us. We are left to make the best decisions we can for our patients. This would matter less if every trust had its own lab and we were dealing with a hospital-based problem. However, we are not. This is a population health issue that we cannot address most effectively as individual providers.

Acute trust

It has been shambolic. The whole pandemic has been run from a government perspective around the 5pm briefing. Delays in staff testing at the beginning… then logistical issues with labs, equipment, reagent etc. which caused lengthy delays in results.

Mental Health and Learning Disability trust

[The government] has overestimated the benefits of centralised and national systems... at the same time the contribution of trusts and public health departments on the ground has been undervalued and (consequently) under-used. We could have mobilised mass antigen testing by the end of March. We could have been testing residents and staff in care homes at that stage. We could have had effective contact tracing in place before then. We should have been testing asymptomatic staff at the height of the pandemic to manage nosocomial spread. With the benefit of hindsight these were MAJOR oversights. What is important now is to learn these lessons properly.

Acute trust