Why is this important?

The way in which health care systems – and people – work is changing. The long term plan set out the need for greater workforce flexibility and coordinated national workforce planning, and was followed by the Interim NHS People Plan’s focus on expanding the workforce and ensuring adaptivity and a more varied skill mix. The interim plan talked of moving to a model where teams of professionals from different disciplines work together to provide more joined-up care, stating that this multidisciplinary approach “will become the norm in all healthcare settings over the next five years” (NHS England and NHS Improvement, January 2019). This continues to develop, with the NHS People Plan 2020/21 outlining Health Education England (HEE)'s plans to support local health and care systems to establish the infrastructure for 'generalist schools' with new training opportunities from August 2021.

The need for multidisciplinary approaches to workforce is increasingly clear from the more flexible career paths that NHS staff are choosing, and from the development of ICSs and the resultant increase in cross-organisational working. Ambulance trusts increasingly employ multiple professions across their frontline roles including nurse practitioners and mental health nurses. The pandemic brought about rapid changes to minimise barriers to these approaches, reducing bureaucracy related to staff movement between employing organisations and different clinical settings, and allowing staff to work to the top of their license. The wider implementation of the digital NHS staff passport, for instance, enabled staff to begin new posts more quickly, and avoid repeated (time-consuming) training. Work is being undertaken at national and local levels to determine how beneficial changes such as these can be retained, but there remain other barriers to realising a multidisciplinary, sufficiently staffed, workforce in the longer-term.

The most significant of these is the lack of a long term, fully costed and funded, workforce plan. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were almost 2,000 vacancies across the ambulance sector. The vacancy rate varied between regions, with some areas as high as 10.8% and other areas as low as 0.5%. The interim people plan projected the need for an additional 2,500 paramedics by 2023, but no funding was attached to realise this figure. Moreover, the sector has serious concerns that this figure is insufficient to cover anything more than attrition, nor does it take into account the increasing role that paramedics are expected to play within the primary care setting, for example with paramedics now included as additional roles in PCNs.

This concern has grown in the wake of the pandemic, with some ambulance trust leaders reporting that staff are leaving their organisations due to burnout, early retirement, or other effects from working in the pandemic. Pressures are being felt by all staff, including those working in emergency operations centres, who are daily facing very visible demand challenges and delayed responses. Retention of staff is arguably a bigger challenge than ever, with recruitment also necessary to meet increasing demand and tackle the care backlog resulting from the pandemic. A fully costed and funded workforce plan is vital to addressing this, but in the interim, ambulance services have been adapting the way they work to begin meeting these challenges.

This includes focusing on areas like increasing mental health expertise within the workforce by bringing in specialist staff. The long term plan made welcome commitments to build the capability of ambulance staff to respond to patients presenting with mental health issues. If adequately resourced, this should help to increase capacity in the system. The necessity of this is clearly shown in figures from 2019, when the London Ambulance Service NHS Trust (LAS) received 168,000 mental health calls and attended over 105,000 incidents caused by mental ill-health – almost 9% of total incidents attended by the service that year. People with mental ill health are more likely to use emergency hospital care than those without mental ill health and 46% of people with a mental health condition also have a long-term physical health condition (King's Fund and Centre for Mental Health, February 2012). Given the reciprocal nature of this link, improvements made to mental health provision often improve patients’ physical wellbeing, and vice versa.

Mental health expertise within the ambulance workforce is particularly important given that EDs are not always the most appropriate place for people in a mental health crisis. While there has been progress in expanding services within EDs to ensure that people in crisis have access to the specialist care they need, the coverage and quality of these services remain patchy. There are still areas of the country where these specialist teams are not available at all times or for all ages, and now that all trusts are under infection control measures due to COVID-19, beds are more limited and wait times are longer. Adapting response models to avoid unnecessary conveyance to hospital for people with mental ill health is, therefore, an important focus for ambulance trusts, but must come hand in hand with the necessary alternatives to ED being in place. These alternatives could also reduce pressure on ambulance services.

There is significant focus on mental wellbeing for staff as well as patients, with funding given to AACE from NHS England and NHS Improvement to progress its collaborative work on suicide prevention within the sector. The work, commissioned by the chief allied health professions officer for England, includes research which demonstrates the increased suicide risk for paramedics, and identifies risk factors which are detrimental to mental health and wellbeing more widely. These factors are the foundation for ongoing action in this area.

How does it work?

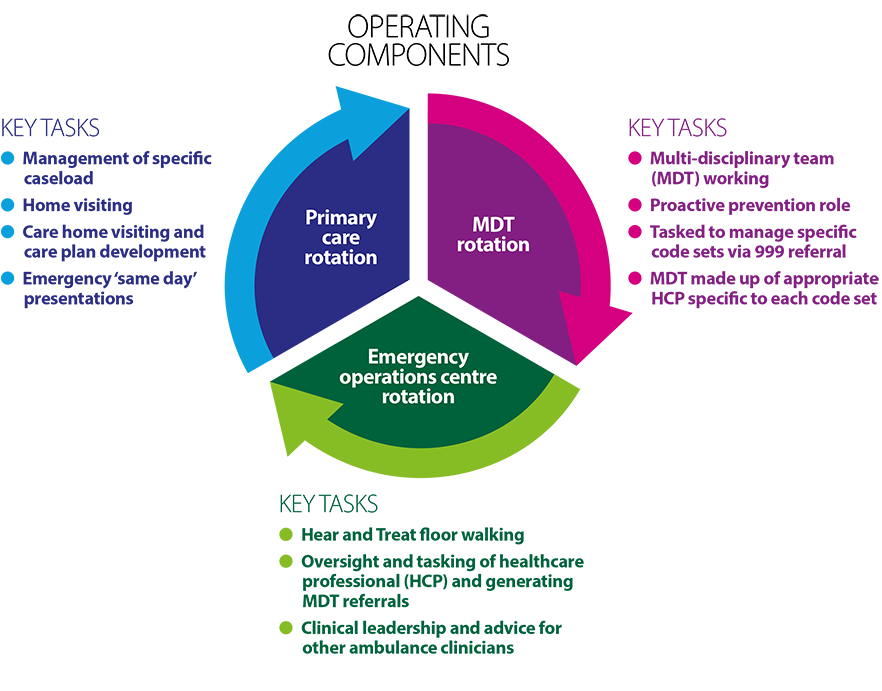

Before the pandemic, trusts were already changing training and working practices so that paramedics can develop and learn alongside other types of healthcare professionals, and therefore be deployed differently. One model of this is rotational working, whereby specialist and advanced paramedic practitioners rotate between clinical settings, using their advanced clinical assessment skills to help provide the right response the first time. This could include working in the clinical hub in an emergency operations centre, or in a CAS providing 'hear and treat' care via telephone consultation, or out with community multidisciplinary teams (MDT), and in primary care. It is particularly notable that this work was already well underway before the pandemic hit, when we saw the NHS flexibly deploying some specialist staff into more general settings during the first peak, as well as a huge increase in telephone and video patient consultations. There have been local initiatives to codify this learning now that the peaks of the pandemic are behind us, such as one trust’s commitment to keep staff who were redeployed and enjoyed the experience involved in one shift per fortnight in their redeployed setting.

The rotational working model used by many ambulance trusts may be a useful blueprint for other providers to use in retaining benefits of increased cross-organisational working from the pandemic. An evaluation of the model has shown it is feasible and could have a positive impact on patient experience, workforce retention and reducing hospital conveyance rates. During a pilot in north Wales, just 30% of patients went to ED, while another 33% were managed without any further referral. The added value of this approach is that trained and experienced staff are kept in the workforce while simultaneously supporting GPs and primary care.

FIGURE 6

HEE's rotational paramedic model

What needs to happen to make this a success?

The rotational model is especially relevant in the context of increased focus on the contribution that paramedics can make to improving capacity and providing appropriate care within primary care settings. Paramedics are now eligible for the PCN Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS), through which they undertake work for a GP practice. Paramedics were added to the ARRS in April this year, but there are outstanding questions regarding how they should be employed, trained, supervised and supported. As such, this poses a number of risks to ambulance workforce capacity and stability and the successful development of the PCN model.

The potential loss of more senior and experienced staff to primary care at a time when ambulance trusts are already understaffed and struggling to recruit to the levels they need is worrying. The service could lose vital mentoring and supervisory capacity, affecting the quality of the whole UEC system given that less experienced paramedics are more inclined to convey patients to ED. Appropriate training must therefore be factored in to equip paramedics with the right skills to manage lower acuity cases in primary care. If appropriately commissioned, the rotational model could also be used to manage this risk effectively, with paramedics continuing to be employed by ambulance trusts which provide the supply to PCNs on a rotational framework. It does not, however, solve the issue of understaffing more broadly. The ambulance sector is committed to working collaboratively with NHS England and NHS Improvement and the PCN network on the next phase of the ARRS roll-out, focusing on lessons learned and monitoring the impact on the ambulance workforce.

Joined-up workforce planning at system and regional level, as well as effective longer-term planning in coordination with the education sector, is essential. We need to see flexible workforce models being supported in the forthcoming updated People Plan (now expected in 2022), alongside a broader understanding across the health sector of the paramedic workforce as a whole – their capabilities and skill sets, and the steps needed to foster equality, diversity and inclusion. This includes ensuring there are sufficient paramedic training places in universities, and supported placements within the UEC system during training, due focus on paramedic retention and ensuring that training and mentoring capacity is created and funded in order to increase the overall size of the paramedic workforce, including for new PCN-supported roles. This has to be undertaken as part of work which is so desperately needed at a national level, for a fully costed and funded workforce plan, based on the practical needs of systems.

To build the capability of ambulance staff to respond to patients presenting with mental health issues, the mental health investment standard (MHIS) has a key commitment to support specific initiatives from ambulance services, for example having mental health nurses in emergency operations centre clinical hubs and CAS. However, there are concerns that money is failing to reach ambulance services due to issues with mental health funding flows, and a wider concern that MHIS may be spread too thinly. In some cases, the MHIS is seen as a maximum limit based on affordability, rather than a minimum based on need. These concerns must be resolved before ICSs can clarify the extent of funding that’s needed to deliver the long term plan’s ambitions in regards to mental health.

Current complex commissioning structures for ambulance services, and the need to link with mental health commissioners to access funding, makes this process more difficult. Coherent guidance is needed as to how ambulance trusts and mental health services should be collaborating in order to make full use of this funding. NHS England and NHS Improvement has developed national commissioning guidance for the mental health ambulance response, which is currently being shared with stakeholders for input before seeking sign off ahead of publication. This must reduce complexity rather than increase it. Capital funding is also crucial for the provision of the right mental health ambulance vehicles, as highlighted in the NHS mental health implementation plan. It will be important for systems to prioritise funding these aspects accordingly, and for funding envelopes to be realistic so that this isn’t an impossible ask.

There are additional recruitment challenges due to a national shortage of mental health staff, both in terms of numbers and skill-mix, which must be addressed as part of wider calls for a fully costed and funded multi-year workforce plan. These shortages are further exacerbated by increased demand for mental health expertise in other areas, not only in the health sector (for example, in PCNs and acute trusts) but in other sectors (for example,. in the justice system, police force, schools and universities). Demand has increased exponentially since the pandemic began, with cases often more complex and of higher acuity. This increase in demand is expected to continue over the months and likely years ahead, so it is vital to get this right.

Where is it happening?

CASE STUDY

North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Community specialty paramedics and new pathways

North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust (NWAS) responded to the national policy direction for integrated UEC being delivered closer to home by developing its team of community specialist paramedics alongside senior clinicians.

These staff members work with external providers to establish and manage community pathways. The pathways are responsive to the health needs of the specific communities they serve and include mental health, respiratory, falls, frailty and – during the COVID-19 pandemic – a focus on social isolation and supporting those struggling to cope with everyday life.

NWAS developed social prescribing referral pathways in partnership with primary care networks and voluntary, community and social enterprise providers. By referring patients to these pathways, clinicians are able to support those patients who, following assessment, have been identified as having low acuity health needs or long-term conditions that need further management by primary care. These patients may struggle with anxiety, loneliness and a lack of support with daily living. Social prescribing practitioners can then work with people to link them to support in their local communities.

One recent patient is Jean, a 71 year old female who lives alone. Recently discharged from hospital following a fall, she had called 999 as she felt unwell. An ambulance crew arrived and, following a medical assessment, were able to establish that she did not have an urgent health care need. However, the crew realised that Jean was struggling with loneliness and to manage her everyday living. With her permission, she was referred to a social prescribing pathway managed by Age UK. Following her referral, she now has support with food shopping, referrals to the local continence and mental health services and to a local befriending service. This proactive, multi-agency, preventative approach is supporting Jean to stay well and should reduce her need to call for emergency support in the future.

NWAS currently has 10 social prescribing pathways in place with more in development. They are exploring how social prescribing pathways could be extended to NHS 111, and used to support high intensity service users. In extending the range of pathway providers to include voluntary, community and social enterprise partners, the care of patients is further promoted within their local community, reducing the pressure on emergency hospital services.

This innovative approach is supported by a dedicated group of community specialist paramedics and advanced paramedics working across the trust.

CASE STUDY

South East Coast Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust

Mental health professionals in emergency operations centres

The South East Coast Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (SECAmb) has introduced mental health professionals into its emergency operations centres to provide expertise on first contact with the service following pathways triage. The initiative, which has formed part of SECAmb's CAS since October 2020, allows the service to ensure that patients presenting with mental health problems have immediate access to mental health expertise from clinicians who are linked into mental health provider trust clinical systems. This means advice and support can be provided to frontline crews on scene, and the need for ambulance attendance and conveyance to EDs is reduced where appropriate.

This initiative has been developed simultaneously with plans to join with two mental health provider trusts in Kent and Sussex to co-locate their single point of access teams in SECAmb's emergency operations centres to work in partnership with SECAmb's mental health professionals. The service now provides 24/7 cover.

Benefits for patients include having initial contact with a mental health professional, being provided with immediate advice and support with appropriate signposting and having contact with a professional who has defined links with the local mental health provider trusts, linking in with emerging alternatives to emergency departments (for example,. safe havens). In the longer-term, benefits are expected to include reduced ED conveyance (where it is not appropriate), increased capacity for frontline crews, and joint working opportunities with local mental health provider organisations.

CASE STUDY

London Ambulance Service NHS Trust

Advanced paramedic practitioners in urgent care

LAS has invested in specialist and advanced paramedic practitioners (APPs) for urgent care, who have undergone extended training in assessing and treating people with medical emergencies. This is a key factor in safely reducing ED conveyance, alongside providing meaningful clinical development opportunities for experienced paramedics increasingly in demand within other areas of the health service. This work aligns to NHS England and NHS Improvement's Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care Services in England, and the 2018 NICE guideline on emergency and acute medical care in over 16s.

HEE funded an initial pilot (and gave subsequent top up funding), and higher education, primary, and urgent care providers work as partners with LAS to support education and training for the initiative. The initial pilot comprised of a small group of trainee APPs in urgent care, who received additional postgraduate education. The trainees worked rotationally within the emergency operations centre and clinical placement settings, as well as the 999 operational environment.

The initial pilot was successful, resulting in an extension of the trial period and recruitment of additional staff. Further evaluation showed that the service was safe and effective, providing lower rates of conveyance compared with a ‘business as usual’ response accompanied by a lower re-contact rate. The trust found targeted dispatch of APPs in urgent care challenging initially, but overcame this by adding a team member within the emergency operations centre.

Funding was necessary to the pilot’s success, in order to procure additional equipment. Initial hurdles in the training programme were overcome collaboratively, with robust assessment and selection methods for recruitment, and by ensuring alignment with the College of Paramedics recommendations and HEE advanced practice definitions.

The service now benefits patients hugely, enabling them to receive care closer to home when accessing the 999 system, and avoiding adverse outcomes associated with unnecessary hospital admission. Ambulance service capability to assess and manage urgent care presentations safely in the community has increased, and is evidenced by low re-contact rates.

Staff are also benefitting from a clear clinical career progression pathway, complementing other pathways in areas such as operational management. The programme enables staff to remain in a clinical role, enhance their career opportunities, and provide more comprehensive care. The APP urgent care programme also avoids dispatch of a dual-staffed ambulance with the associated costs in favour of a single responder less likely to convey the patient to hospital. This has resulted in job cycle times being lower overall, and ambulances are available to respond to other calls.

Further upscaling of the service has the potential to further reduce unnecessary conveyance, reducing pressure on EDs and reducing ambulance handover delays. APPs working in the emergency operations centre are also able to perform additional roles, such as providing telephone advice to patients. The service is now due to expand, with the addition of further trainee APPs to improve consistency and times of operational cover across the trust, and is replicable across all ambulance trusts given the appropriate support, level of education, and system-wide buy in.