Summary

The greatest asset the NHS has is a committed and caring workforce. Colleagues across the health and care sector agree on the need for cultural change to ensure the NHS workforce is as diverse as the population it serves, to address bullying concerns and to ensure leaders model collaborative and supportive behaviours within national bodies and regional teams, as well as at the frontline. Yet, workforce challenges are among trust leaders' greatest concerns with staff shortages and a historically confused approach to national strategic workforce planning affecting providers' ability to offer sustainable services.

June 2019 saw the publication of the NHS interim people plan which will be consolidated into a final people plan. The interim people plan sets out approaches for improving the NHS working environment, strengthening the leadership culture, tackling nursing shortages and future-proofing the workforce.

Provider leaders also have a significant role as key players in new health systems working to articulate local workforce requirements and implement more locally rooted workforce strategies. As part of this task, they will ensure that workforce strategies reflect new ways of providing health and care, and that organisations are able to deploy staff in a way that best reflects the skills mix needed to provide effective and efficient services for their communities.

The Provider Challenge

Making the NHS the best place to work

Reflecting the challenge of high vacancy rates and worrying signs of stress and burnout at the frontline, the starting point for the interim people plan is that the NHS needs to be a better place for staff to work. This relies on leaders at all levels modelling the right behaviours. It also means ensuring the NHS offers attractive package of pay, terms and conditions, flexibility, work-life balance, and career progression to new joiners and those within the service.

Building an inclusive culture built on staff engagement

The interim people plan has made a commitment to set out what staff can expect from the NHS as an employer. This includes fostering a healthy workplace culture, a focus on promoting inclusion and widening participation, action to tackle bullying, harassment, violence and abuse, and career development and education goals. Importantly, there will be an emphasis on whistleblowing and speaking up, as well as work to improve physical and mental health, and to reduce sickness absence. It also emphasises work to improve the leadership culture within the NHS and proposes that as the NHS shifts to greater system collaboration, it will necessitate "systems-based, cross-sector, multi-professional leadership, centred around place-based healthcare that integrates care and improves population health".

A diverse and inclusive workforce is critical to providing high-quality care. Different studies demonstrate the strong link both between diverse and inclusive leadership, with a diverse and inclusive staff team, and quality of care (The King’s Fund, 2015). To date there have been a number of initiatives and approaches – such as the workforce race equality standard (WRES) – to seek to improve representation of black and minority ethnic groups in our workforce which have made some progress. The WRES approach is now being extended across other protected characteristics, including implementation of the disability equality standard (DES).

However, we need to go further and faster in ensuring that NHS boards and staff across the health and care workforce are reflective of the diversity within our population. The forthcoming NHS people plan therefore needs a strong focus on inclusion and diversity, with clear and specific actions and proposals.

- Aspects of last year's NHS staff survey with regard to bullying and harassment and stress and wellbeing make for worrying reading:

Although almost 72% staff respondents said they received the respect they deserved from colleagues, less than half (45%) said relationships were never or rarely strained at work. - Almost one in five respondents (19%) experienced bullying by a colleague in 2018 – an increase of more than 1% on the previous year’s figure of 18%. The proportion of staff experiencing bullying by a manager was 13%, slightly up from the previous year’s 13%, and 28% of respondents reported bullying by a patient, service user, family member or other member of the public, compared with 28% the previous year.

- Almost four in 10 staff (39.8%) reported feeling unwell at work in the last year as a result of stress and 27.6% experienced musculoskeletal problems in the last 12 months as a result of work activity. Only a minority (29%) said their trust definitely takes positive action on health and wellbeing.

- Three in 10 staff (30%) said they often thought about leaving their organisation.

Maintaining morale and wellbeing at work is central to recruitment and retention across the service but continues to prove a challenge to many trusts as demand for services rises relentlessly year-on-year, with widespread vacancies, pressing shortages in particular professional groups, and staff members becoming increasingly stretched. Anecdotal feedback from trust leaders this year has consistently reflected the fact that the NHS is reliant on the discretionary effort of its committed staff to function at times of pressure. Trust leaders say that this winter, they do not expect to rely on that discretionary effort as individual members of staff, quite understandably, can no longer sustain the additional hours they have offered to patient care.

We have significantly reduced our agency spend and increased the usage of our own bank staff who like to work flexibly. However, there remains a shortage of qualified nurses in mental health, learning disability and community/district nursing which is being outpaced by the numbers of experienced nurses retiring or leaving the NHS because of work pressures.

Combined Mental Health / Learning Disability and Community Trust

Pay, terms and conditions

Ensuring appropriate pay, terms and conditions is central in enabling the NHS to recruit and retain the talented and committed workforce it needs to sustain high quality patient care. We continue to make the case to the pay review bodies for appropriate uplifts for senior staff and those on Agenda for Change. Recent movement in renegotiating the junior doctors’ contract has also been welcome.

For senior medical and managerial staff, the most pressing issue this year has been NHS pension arrangements (British Medical Association, 2019). Significant tax bills arising from the interplay of the annual and lifetime allowances and the annual tapering tax relief threshold introduced in 2016 have acted as a disincentive to taking on more hours and even driving people to reduce their hours, reject promotion or take early retirement. The impact on trusts has been to reduce the size of the pool of clinicians available to take on extra work to sustain urgent and emergency care and other seven day services, and to keep waiting lists down.

However, the issue equally impacts managers within the NHS who are taking on complex leadership positions, including at board level which carry significant accountability and responsibility. It is also relevant to all staff within the NHS, including more junior members of the scheme and to ensuring an equitable approach across the NHS family. While the government's current consultation on the NHS pension offers much greater flexibility, and the Treasury’s review of the annual taper is welcome, there is much more to do to ensure NHS pensions arrangements do not directly impact trusts’ ability to staff and provide sustainable services.

We are seeing increased pressure in parts of the clinical workforce - notably doctors, due to actual or perceived pension tax issues. This is on top of significant supply challenges in a number of key specialties. While we are creating innovative ways to respond, these will take time to resolve.

Acute Trust

Tackling workforce shortages

Although there are staffing shortages across the NHS, including in key areas such as learning disability services, mental health and for some community services, the lack of nurses across all services is the most concerning. In March 2019, there were 39,520 full time equivalent nursing vacancies in NHS trusts and foundation trusts, and thousands more across general practice, social care and the independent sector. This compares to slightly fewer than 9,183 medical staff vacancies in the trust sector. The Health Foundation, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust have projected that on current trends, in 10 years' time, the NHS will have a shortfall of 108,000 full-time equivalent nurses. Additionally, successful applications to undergraduate nursing courses have lagged behind government targets, with the number of placed applicants in 2018 4% lower than in 2016.

A number of factors influence the 'pipeline' of professionals entering the NHS. These include funding for education and training, political and national policy decisions such as subsidies for nursing and medical degrees, and the sophistication of national, regional and local workforce planning.

Immigration policy from within the European Union (EU) and beyond is also critical for the NHS and wider health and care system. The health think tanks point out that concerns about Brexit have created extra short- and medium-term risks. A net inflow of nurses from the EU turning into a net outflow – between July 2017 and July 2018, 1,584 more nurses and health visitors from EU countries left their roles than joined (NHS Digital, 2018).

In response to these challenging figures, the migration advisory committee recommended in May 2019 that all medical roles should be placed on the shortage occupation list, and that nurses should remain on the list. However, a new level of uncertainty has been introduced with the committee’s decision to review both salary thresholds and – crucially – a potential points-based future immigration system, favoured by the current government. The criteria for "points" in a future system, and the overall nature of migration into the UK from 2021 and beyond, is unclear.

For a trust, a shortage of nurses and other staff groups has the potential to affect the quality of patient care significantly, with increased waiting times, potential risks to safety and patient experience. In order to counter these risks, provider organisations find themselves spending increasing sums on bank and agency staff, which is an expensive solution to an enduring problem. In the 12 months ending March 2019, the provider sector spent £3,445m on bank staff (£666m or 24% more than planned) and £2,401m on agency staff, which was £201m or 9.1% above plan (NHS Improvement, 2019b).

Finally, the development of system working, and primary care networks (PCNs) at a neighbourhood level has the potential for local partners to develop more flexible working models with the possibility of offering staff 'passport' arrangements to work across sites within a geographical area, and more innovative career paths to attract people to join and stay in the NHS. However, these developments also raise a challenge for ambulance and community providers in particular who are keen to ensure well intentioned recruitment by colleagues in primary care does not destabilise the local labour market and existing recruitment strategies.

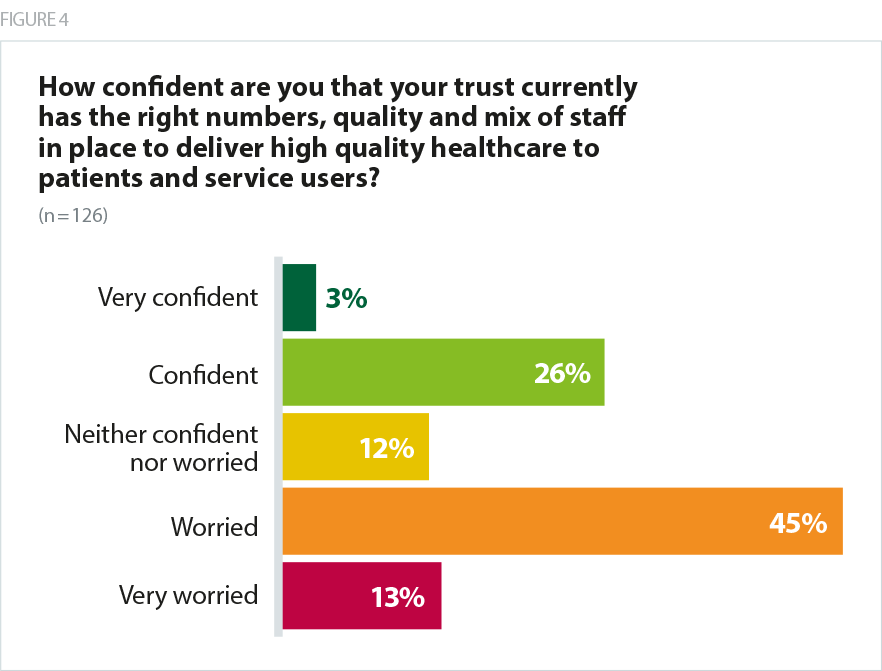

Concerns over staffing were reflected in trust leaders’ responses to our survey. Only 29% of survey respondents were confident that their trust currently had the right numbers, quality and mix of staff in place to deliver high quality healthcare to patients and service users, and almost six in 10 (59%) were worried that they did not have this in place. This is a slight worsening compared with 2017 when 56% were worried. Levels of confidence decreased as respondents were asked to look forward to future years, with only 18% saying they were confident of the right numbers, quality and staff mix in two years’ time.

Staffing remains a concern for the board. The current staffing position, particularly on nursing overall, is good with very low agency use, but there are specific skills shortages, particularly in paediatric nursing. There are also skill shortages in other professional groups. A range of factors including the potential impact of EU exit and the impact of tax policy on NHS pensions are also significant concerns in terms of the trust's ability to deliver patient services.

Acute Trust

Removal of the nursing bursary hasn't helped. Attracting and retaining high quality registered staff is difficult.

Mental health / learning disability trust

With the plan to recruit large number of paramedics into primary care there is a major risk this will lead to significant workforce and skills mix challenges in ambulance trusts.

Ambulance Trust

Workforce devolution

Trust leaders have generally had limited opportunity to intervene in workforce strategy beyond their own organisations. The interim people plan opens the door to significantly increasing devolution of strategic decision-making about workforce. The mechanism for achieving this devolution is a “new operating model” that would see responsibility for different aspects of workforce strategy shared between the arm’s length bodies, the regions, ICSs and local areas within ICSs.

This shift in focus is likely to be good news for provider organisations wanting to work with peers to ensure that approaches to workforce development are better suited to local and regional need. But although the plan recognises the need for extra resources to flow to ICS level alongside the extra responsibilities, the detail of how this will work is yet to be confirmed, and part of the engagement work underway under the umbrella of the people plan. Providers have also expressed concern about the lack of focus in the plan on the role of local government, and by extension social care, particularly if workforce plans are to reflect long-term population health trends.

Transformation and skill mix

The interim people plan also seeks to increase the flexibility of the NHS’ approach to workforce planning by enabling professionals from different disciplines to work more closely together. Providing care in a more joined-up way becomes particularly important as the number of people living with multiple long-term conditions increases, as these patients will access services provided by different organisations and teams at different points in their treatment.

NHS England and NHS Improvement has recognised through its interim strategy that to move to a multidisciplinary way of working will require changes in how staff are trained and deployed, as well as cultural changes to ensure that mutual trust, respect and understanding can exist across different settings, and between services provided by the NHS and organised as part of local authorities’ social care provision.

It is proposed in the plan that the skill mix of the health workforce will be enhanced through scaling up the development and implementation of new roles and models of advanced clinical practice, and by providing clear career pathways to enable people to continue developing professionally. The introduction of both new technologies and more personalised care will also require new skills. NHS England and NHS Improvement acknowledge that to achieve this will require investment in new roles and regulatory attention in the form of amended professional standards and systems of professional regulation.

They propose the development of multi-professional credentials to help staff widen their knowledge and develop new skills. These are to be used alongside the apprenticeship levy, which it is hoped will expand the number of routes into healthcare careers, and a further 7,500 spaces will be made available to train for the new nursing associate role.

However, these plans follow a prolonged period of cuts to the budget for continuing professional development, which is critical in enabling trusts to retain and upskill their staff. That budget dropped from £205m to £83m in 2015 and now stands at £119m. Moreover, recent data shows a drop-off in levels of participation in the government's apprenticeship scheme – a decreasing of 9.8% across the board in 2018/19 – compared with the previous year.

How providers are responding

Providers are working collaboratively, and with other local partners within STPs and ICSs to create innovative career pathways in support of staff recruitment and retention, and to ensure staff can work flexibly across a local area to meet demand. The trusts and partners within Greater Manchester developed a health and care workforce strategy for the system to help address workforce challenges across ten localities. Other examples include the development of collaborative arrangements for staff passports by a group of six trusts in the west Yorkshire and Harrogate integrated care system, or the use of a shared nursing bank and a medical collaborative bank in south Yorkshire and Bassetlaw.

Trusts continue to address vacancy rates with innovative recruitment approaches. Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust has been recruiting nurses from Dubai and the Philippines successfully for the past two years, without outsourcing, and is now supporting 12 other trusts with international recruitment.

Trust boards are fully committed to supporting their staff through a range of initiatives including quality improvement programmes which empower staff to lead quality improvement from the frontline and support staff wellbeing. Examples include Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust's initiatives to support staff wellbeing which have in turn had a positive impact on retention and the work undertaken at Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust to offer staff a range of non pay benefits and support.

What does this mean for patients and service users?

Committed and caring staff are the bedrock of the NHS. We owe every member of the NHS staff team a duty of care and must invest sufficient leadership and management time, and resource, to protect their wellbeing, and support them to manage the inevitable stresses and emotional strains of working within a care setting. We also know that there is a clear correlation between investment in staff engagement and wellbeing, and the quality of patient care.

The number of workforce vacancies facing the NHS, gaps in particular skill sets, growing reports of bullying and harassment and a growing concern about ‘burn out’ therefore has a very direct impact on the quality of care which patients and service users experience.

Gaps in rotas and vacancies have a direct impact on patient care including delays to elective procedures, a poorer patient experience and even safety risks. Use of bank and agency staff to fill rota gaps, can carry associated quality implications and crucially eats into trusts’ funding for other priorities.

However, sufficient investment in a 'just' and transparent culture within the NHS has an equal, if not greater, direct relevance to quality of care. All staff should feel supported and empowered to raise and act on issues of concern without fear of blame, and to support their colleagues in a culture of learning and continuous improvement.