The existing fragmented NHS pattern of service delivery is no longer fit for purpose and trusts recognise the need for transformation. Trust leaders support the idea of system-based planning and the vision outlined in the NHS Five year forward view of moving to new ways of providing care, including accountable care organisations and systems. They see the integration of health and care as a potential means of addressing the challenges of rising demand, responding to the growing number of individuals with more complex health needs and improving health outcomes. New care models are making good progress in transforming care and are gathering pace across the country, but they still only cover small areas and are limited in scope. And there is no compelling evidence that they will deliver long-term financial savings or reduced hospital activity.

There is support for the concept of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) as a means of delivering these changes but there are some key barriers to overcome. We also need transformation to move faster while also being realistic about how long it will take to deliver these changes.

The provider challenge

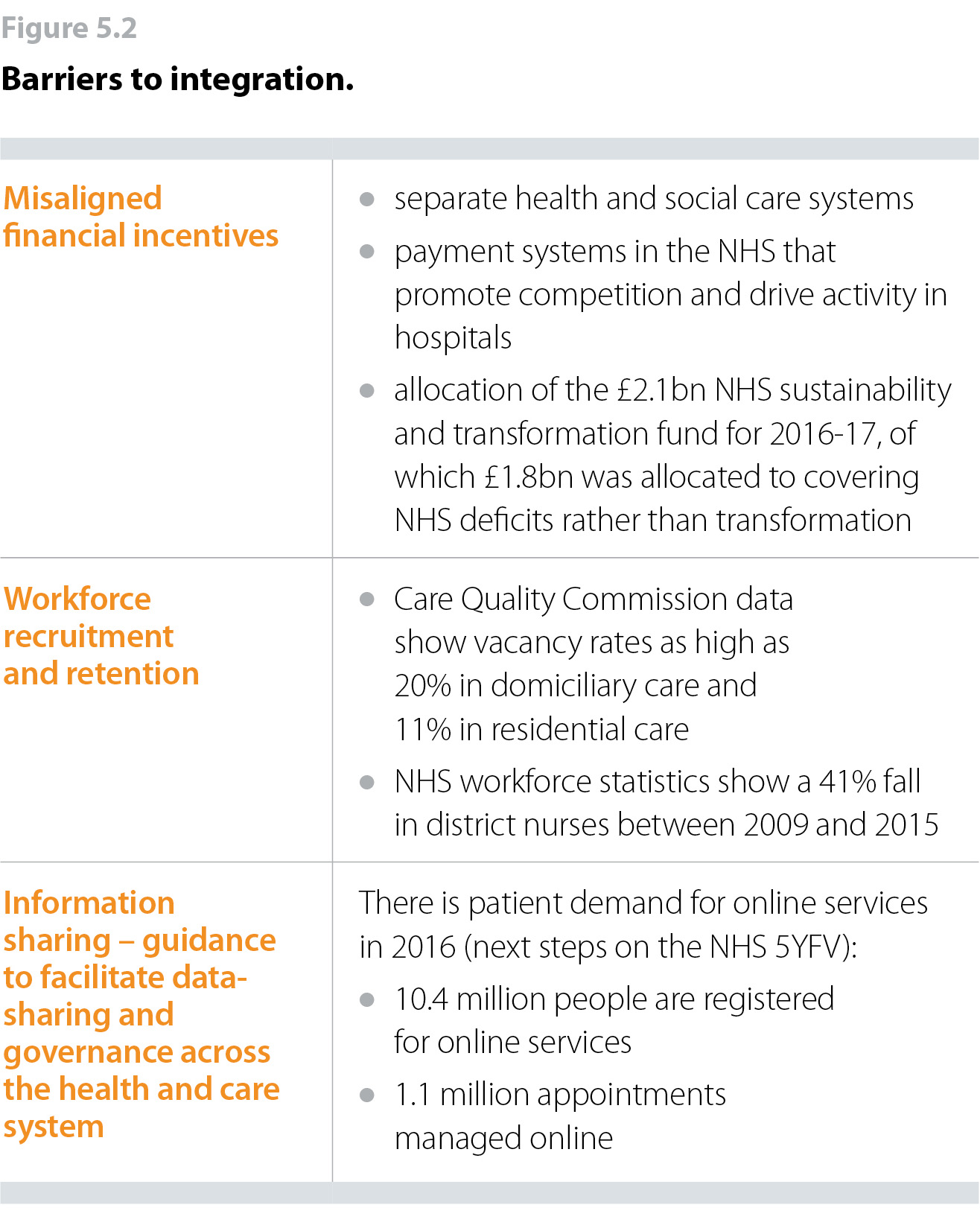

Given the diversity of the NHS and the range of different perspectives within it, there is a remarkable degree of agreement, thanks to the NHS Five year forward view, on the nature of the transformation the NHS needs to undertake. Figure 5.1 sets out some of the key changes the NHS needs to make:

The NHS Five year forward view, launched in October 2014, is now 1,000 days old. How effectively is the NHS delivering the vision it contained?

New care models

New care models are making good progress in transforming care and are gathering pace across the country. However, they still only cover small areas and are limited in scope (either covering one health condition or one demographic such as older people). The early impact of the 50 vanguards is encouraging as there is good evidence of improved patient outcomes. For example, Sutton Homes of Care’s “Red Bag” innovation has reduced average hospital lengths of stay by four days. However, there is little evidence so far, of financial and efficiency benefits.

This is confirmed by a recent Nuffield Trust review of emerging STPs combined with an analysis of 27 initiatives to move care out of hospital. This concluded that while many of these initiatives have the potential to improve patient outcomes and experience, many would not deliver savings and some actually increase overall costs.

A recent National Audit Office (NAO) report also confirmed that integrated models of care can improve patient experiences and outcomes but that there is no compelling evidence of long-term financial savings or reduced hospital activity. The NAO also examined the Better Care Fund, one of the key government initiatives to integrate health and care, and concluded that it has not achieved the expected value for money in terms of savings, outcomes for patients or reduced hospital activity.

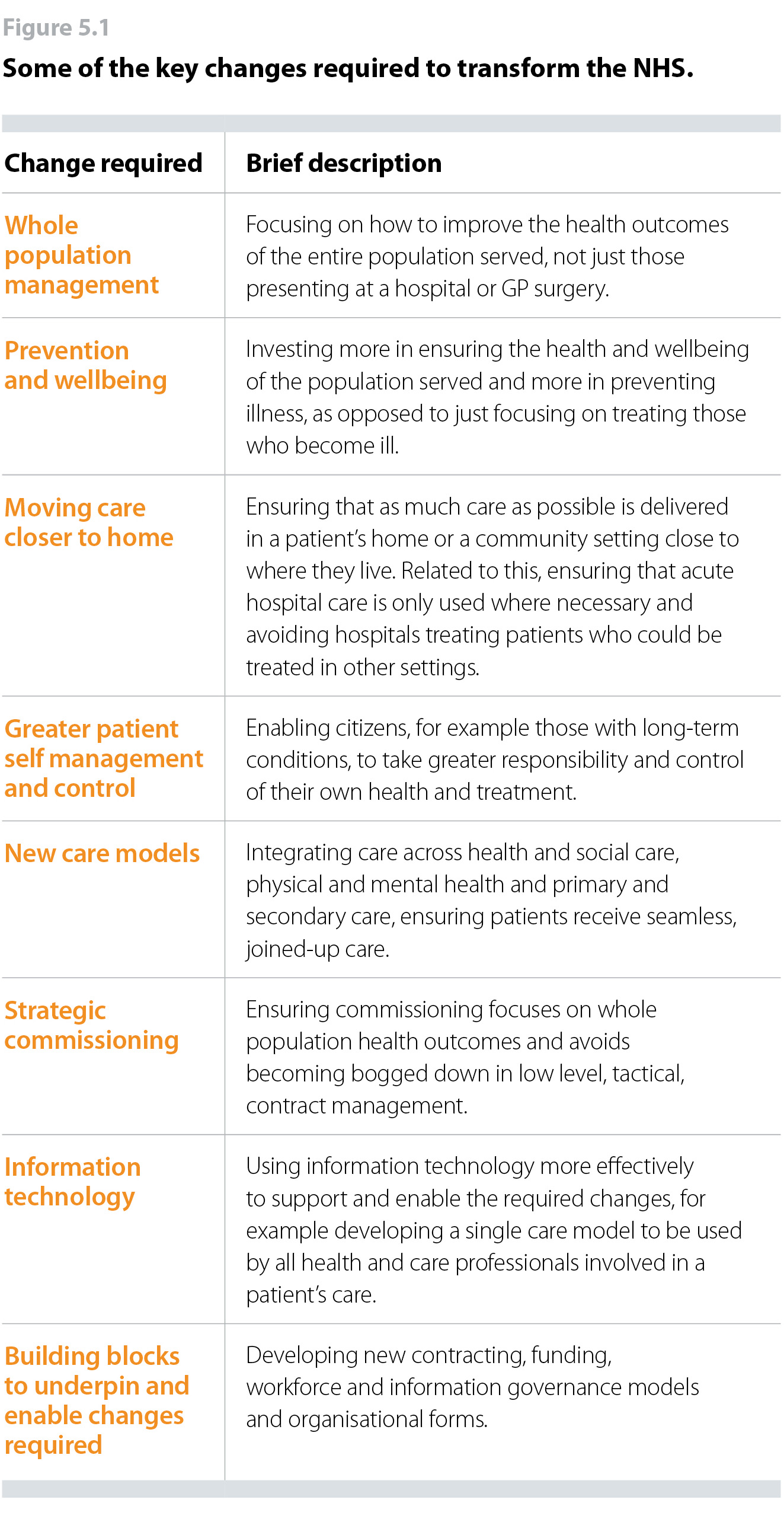

The report highlighted a number of barriers to achieving integrated care, including misaligned financial incentives, the need to change workforce profile and the need to share information.

It is worth noting that, on the ground, actual patterns of NHS service delivery are moving away from the agreed direction of travel set out in the NHS Five year forward view, for example its goal of strengthening community-based services and focusing on prevention. Recent research by The King’s Fund found that financial pressures are having the greatest impact on essential support and prevention services including genitourinary medicine and district nursing. Many of the cuts that have been made, including cuts to preventative services, are storing up problems for the future. An NHS Providers survey in late 2016 also found that intermediate community service capacity such as step up and step down beds was being reduced rather than increased despite the NHS Five year forward view vision of moving care out of hospital into the community. The King’s Fund’s research also found instances where innovation was stifled because of the necessary funding, staff time or skillset being unavailable.

In other words, whatever the strength of the vision and the degree of agreement behind it, the NHS risks being pulled in the wrong direction through pressure on financial and staffing resources. We also still do not have a clear and robust delivery plan on how the NHS, in every local system, will move from a small number of vanguards into consistent adoption of new care models across the country.

Devolution

Greater Manchester continues to lead the way on taking devolved control of its £6bn annual health and care budget. Considerable progress has been made in defining a strategy, setting up governance structures and identifying appropriate change programmes. Early changes such as the consolidation of the provider sector and plans to move to a single model of acute services are now in place. However, it is still too early to judge the ultimate success of this bold experiment. NHS England has recently announced a devolution health deal for Surrey, but other areas that initially declared an interest in a devolution health deal have since fallen away.

STPs

STPs continue to be a key driver of local transformation. The Next steps on the NHS five year forward view outlined NHS England’s and NHS Improvement’s intention to allow different STPs to move at different speeds. Sensibly, the fastest will be able to progress without delay but others will not be forced into adopting a single uniform approach that they are not ready for.

The Next steps report set out an expectation that the most advanced STPs will evolve into locally integrated health systems – these are being called ‘accountable care systems’. The first eight systems, recently announced, will be expected to have collective decision making and governance structures to oversee transformation. In time, some will become accountable care organisations, where a single organisation provides or oversees the majority of health and care services for a local area.

However, while there is support for the concept behind the STP process, trusts and other independent commentators have concerns over how achievable the plans are within the available timescales and funding levels. The Nuffield Trust for example has warned that the falls in hospital activity projected in many STPs will be “extremely difficult to realise”. International experience, for example from American integrated care organisations and Ribera Salud in Spain, suggest that successful development of the kind of models being targeted takes 10 to 15 not three to five years.

The governance arrangements of STPs have been a long running concern for trust leaders. The Next steps report began to recognise the importance of existing governance and accountability structures, but also the opportunity for shared decision-making at the STP level. It also recognises that the 2012 Health and Social Care Act prevents the creation of a formal ‘mid-level STP tier’ with statutory powers.

In summary, while there are early signs of progress in a small number of new care models and in a small number of leading STPs, the overall sense is of an NHS struggling to change at the speed required.

Our latest survey of chairs and chief executives reinforces these concerns by revealing there is little confidence that local transformation is happening quickly enough. Almost two-thirds (62%) of leaders are worried that their local area is not transforming quickly enough. Fewer than two in 10 (17%) are confident that this is happening.

Figure 5.3

What providers need

NHS providers recognise the need for rapid transformation as set out in the NHS Five year forward view. To speed up the pace of change, trusts need:

- much enhanced leadership capacity at the frontline to deliver the required transformation alongside the task of providing outstanding day to day care in an increasingly unstable context where demand is rising rapidly

- a capital plan that reflects the fact that no other sector has ever attempted transformation on this scale without proper funding

- some risks will need to be taken, including turning the arms length body model on its head – from an approach based on assurance and regulation to one that supports and enables change and transformation

- continued funding for the vanguards given their job is only three-quarters complete. The vanguards are still creating key transformational building blocks such as new contracting and funding models; new information governance approaches to enable joined up care records and new workforce models. They need targeted funding for at least one more year to ensure the task of creating these key building blocks for others to use is completed

- clarity on where we are headed with STPs. If they are to be our main vehicle for transformation, we need much greater clarity on their longer-term status as the current picture is confused.

National political and system leaders will also need to be realistic about the pace at which STPs can deliver change. Progress will vary across the country depending on the strength of the plans. Alternative plans should be developed where a more credible set of proposals are needed.

Adequate investment and additional capacity in community services is needed to support programmes and initiatives that attempt to manage demand. Any attempts to shift significant amounts of care closer to home will require additional supporting facilities in the community, appropriate workforce and strong analytical capacity. These are frequently lacking and rely heavily on additional investment, which is not currently available.

STPs have received criticism for the way in which they were produced and perceptions of a lack of meaningful engagement with the public, health care staff and others such as governors and non-executive directors. Trusts will need to be supported to communicate and engage their local communities in the proposed changes.