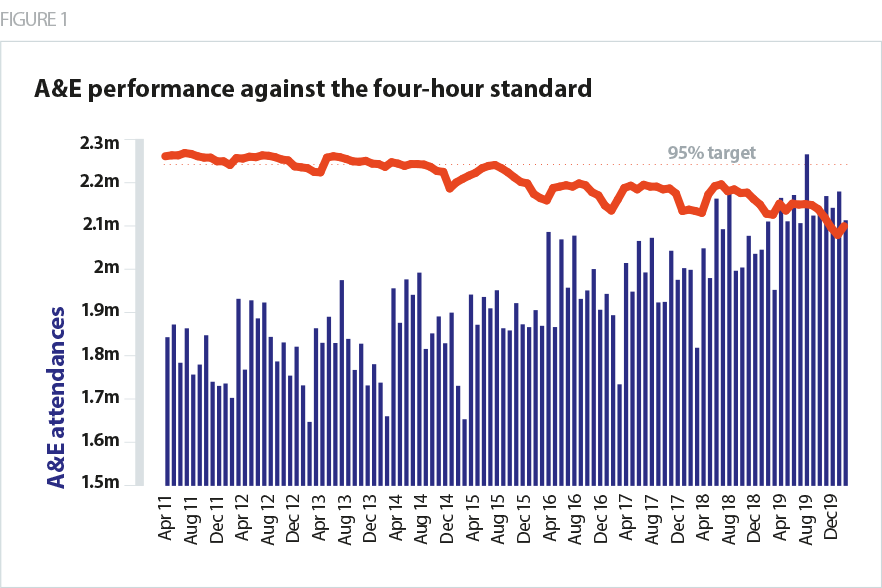

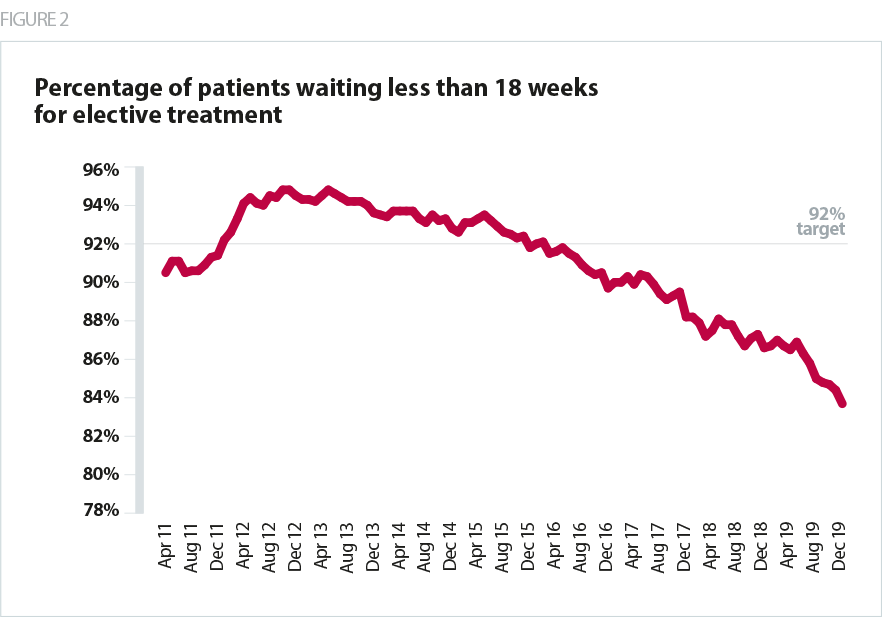

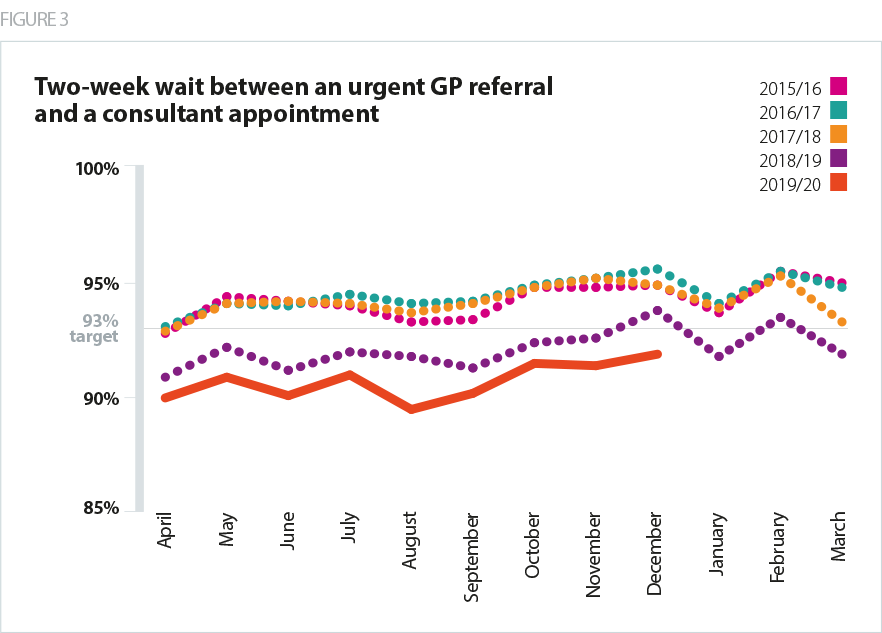

Parts of the NHS in England are experiencing the worst performance against waiting times targets since the targets were set. Performance has steadily deteriorated over the past six years. This includes the highest proportion of people waiting more than four hours in A&E departments since 2004, and the highest proportion of people waiting over 18 weeks for planned hospital care since 2008. People are also waiting longer for diagnostic tests and to access cancer services than they were several years ago.

These challenges are not unique to England, and performance against the standards has slipped across the UK. People are waiting longer for treatment as a direct result of the fundamental mismatch between capacity and demand. A growing and ageing population has fuelled rapid increases in demand for care compounded by a decade of much lower than average funding growth in the NHS and workforce shortages.

This has four consequences which are important when reflecting on the changing context in which we need to review the use of access standards:

- Some standards have effectively lost their relevance and become inoperative as a means of managing performance and motivating staff. If it’s impossible to achieve the standard, they become redundant for these purposes.

- The inability to achieve the standards condemns the NHS to the ongoing narrative of failure, irrespective of how hard or effectively NHS staff are working. We must be cognisant that this may undermine public confidence in services.

- This makes a debate about changing access standards more tricky and complex because there will obviously be a perception that the standards are being changed because they can no longer be met, however strong the case for clinical change. This reinforces the need for a broad and wide consensus across all the relevant audiences on how and why any changes are being made and how the range of purposes they have filled to date will be met.

This also means that, to carry credibility, any changes need to be clear and explicit about the inherent performance levels being aimed for in relation to the existing standards. This is clear in the proposed changes to the cancer standard – an explicit improvement is being sought compared to the current standard. This is less clear in the proposed direction of travel on the A&E and elective surgery targets. Linked to this, if the new standards are proposing to improve (e.g. cancer) or recover lost performance (e.g. A&E and elective surgery), then any change must be accompanied by a clear, fully-funded and planned, credible, performance improvement plan and trajectory. This is particularly important at a point where some believe that there is already insufficient workforce and money to deliver the priorities in a long term plan that lacks a detailed performance trajectory. Changing any standard will not, by itself, improve performance.