The operating environment for the provider sector as a whole is fundamentally changing. There has been a major shift – first set out in the Five year forward view and most recently reinforced by the long term plan – towards NHS and local authority organisations working in ‘place-based’ partnerships, in order to deliver services in a more integrated way to meet the changing needs of the population and ensure they are sustainable. This approach to transformation is being delivered through sustainability and transformation partnerships and integrated care systems.

Against this back-drop of local system changes, mental health trusts have been contending with rising demand for services and increasingly constrained funding. Despite significant and welcome additional investment, mental health money is not always making its way to the frontline services that need it most. Trusts also face specific, longstanding challenges around payment systems and commissioning arrangements, which impact the quality and efficiency of services and the continuity of people’s care.

Given this context, we asked mental health trust leaders for their views on funding, payment systems, commissioning arrangements and moves to system working and their impact on the current – and future – delivery of services.

Despite significant and welcome additional investment, mental health money is not always making its way to the frontline services that need it most.

tweet this

Funding

The long term plan makes a welcome commitment to growing investment in mental health services faster than the NHS budget overall for each of the next five years, so that mental health will receive a growing share of the NHS budget worth at least £2.3bn a year in real terms by 2023/24. However, NHS England has since confirmed that funding for mental health will only rise as a share of the NHS budget by 0.5%. (NHS England, Allocation of resources to NHS England and the commissioning sector for 2019/20 to 2023/24). The size of the rise in funding for the sector falls far short of the amount needed to close the proportionate gap between funding for physical and mental health care and raises questions over what mental health providers can realistically be expected to deliver as a result.

For some time there have been concerns that funding for the mental health sector is not always making its way to the frontline services that need it most. This has meant mental health service budgets are under strain to meet new access standards, deliver the priorities originally set out in the Five year forward view for mental health and provide their core community services. The pressures of increasing demand for both adult and children’s mental health services have also been exacerbated by the deepening cuts to local authority funding.

These funding pressures are reflected in the views of frontline trust leaders:

- 95% of trust leaders disagreed or strongly disagreed that overall investment in mental health is adequate to meet current and future demand

- 65% did not think that their trust has the freedom to invest in the areas they identified as a priority

- 60% disagreed with the statement ‘my trust is able to balance meeting the requirements of national policy priorities while providing core mental health services’ while only 15% agreed

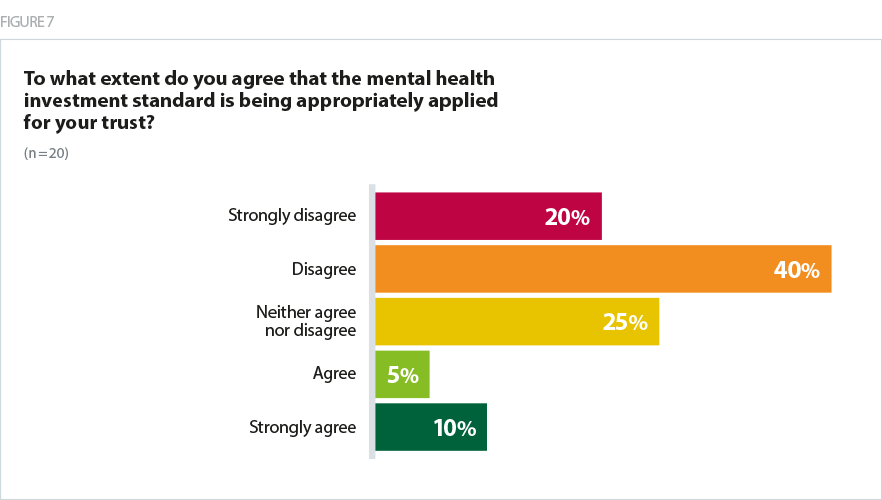

- 60% disagreed with the statement ‘the mental health investment standard is being appropriately applied for my trust’, as shown in figure 7, while only 15% agreed with this statement

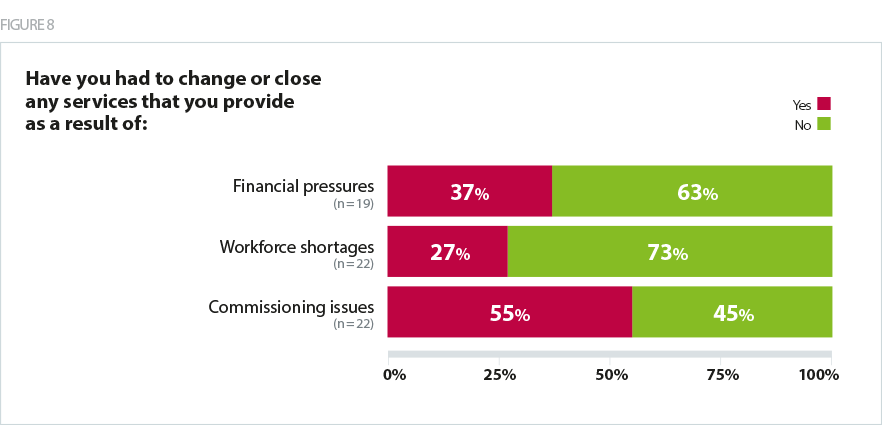

- 37% of trust leaders said they had to change or close services as a result of financial pressures Examples of services affected included closing alcohol and substance misuse services, homelessness services and some inpatient services.

The reports of spending by CCGs are not transparent. I cannot see where all mental health spend is made and so cannot verify that mental health investment standard (MHIS) is being met. New money is earmarked for new services and there is insufficient uplift to meet demand in core services.

Mental health trust

Given trust leaders’ concerns about funding flows, we welcome NHS England’s proposals to tighten rules for CCG spending on mental health services and implement stricter controls on those failing to achieve the mental health investment standard in its planning guidance for 2019/20 (NHS England, 2019b). Further moves by NHS England to increase transparency in the way mental funding is allocated from CCGs to mental health trusts is accounted for are also welcome - this must be tightly monitored and enforced.

The support for the MHIS has been really positive and changed the dynamic of the relationship with commissioners who are now looking to agree the best way forward to develop this

Mental health trust

Payment systems

Our survey highlights that the way many NHS mental health trusts are being paid to deliver the majority of their services – through block contracts – has long been a key challenge for many trusts, despite a commitment by NHS England to phase out unaccountable block contracts. Mental health service leaders have said this would be the most effective way of alleviating pressures on services within the next two years, and that block contracts also act as a key barrier to reducing out of area placements – a key national ambition.

Given these findings, it is encouraging that NHS Improvement and NHS England are proposing blended payment systems become the default for adult mental health services for the national tariff for 2019/20 (NHS Improvement and NHS England, 2019). This new approach has the potential to support the much-needed expansion and enhancement of mental health services. However, it will be important to recognise that setting a baseline for activity will be difficult, potentially time consuming and is likely to require a significant resource commitment. Providers are also concerned about the lack of prior engagement on the detail of these proposals, and that the timescales for implementing such significant changes to mental health contracts are too short.

Our survey highlights that the way many NHS mental health trusts are being paid to deliver the majority of their services – through block contracts – has long been a key challenge for many trusts, despite a commitment by NHS England to phase out unaccountable block contracts.

Commissioning arrangements

The complex – and often fragmented – way in which mental health services are commissioned has been a longstanding issue for trusts and has significantly impacted both the efficiency of service delivery and the continuity of care. The key challenges stem from the split in commissioning responsibilities between local and national NHS bodies, following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, alongside the transfer of the commissioning of wider services – ranging from substance misuse to school nursing – to local authorities.

Our latest survey of mental health trust leaders puts this challenge into sharp focus, with over half of respondents stating they had changed or closed services as a result of commissioning decisions. Commissioning arrangements were also cited as a key reason why trusts are struggling to meet demand.

As figure 8 shows above, 55% of mental health leaders said they had changed or closed services due to commissioning issues. Examples they provided included:

- closing homelessness service

- closing rehabilitation beds

- reducing inpatient detox beds for alcohol/substance misuse

- withdrawing mental health primary care provision.

When asked what changes would most alleviate the pressures on services, trusts leaders said:

- ending block contracts

- delegating commissioning to providers

- reducing tendering activity

- investing in core services beds and community mental health teams, assertive outreach, crisis care, CAMHS.

- Incentives to increase the workforce

- Capital for investment in estates

Welcome work is underway to bring together fragmented commissioning arrangements and support more integrated working, with the introduction of new models of care as first set out in the Five year forward view. For mental health, these new models have enabled secondary providers of mental health services to manage care budgets for tertiary mental health services, such as secure services or specialised services for children and young people.

An increased focus and commitment on mental health and community services as a genuine priority from the centre, with associated funding including capital.

Mental health trust

Moving away from block contracts, towards outcomes based commissioning frameworks, was also singled out by mental health leaders as a local commissioning change that would have a positive impact on services and most effectively alleviate pressures on services within the next two years.

A number of leaders stated that the consolidation of the CCG landscape and work at a system level would improve the effectiveness of commissioning. This suggests that the intentions set out in the long term plan to reduce the number of commissioners across systems align with what mental health trusts need to be more strategic and efficient and are therefore a welcome step forward. It is important to note, however, that one respondent stated the merging of group budgets under STPs could have negative consequences and that capitation is needed.

Other commissioning changes that trust leaders said could have a negative impact on their services within the next two years included a reduction in budgets and the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) programme related to all adult mental health services, which could result in unhelpful disinvestment.

A number of leaders stated that the consolidation of the CCG landscape and work at a system level would improve the effectiveness of commissioning.

Transforming Care

The lack of clarity over commissioning responsibilities between CCGs and NHS England was also highlighted as a barrier to trusts making progress on transforming care – the national programme aimed at improving health and care services for people with learning disabilities and autism in community settings and closer to home.

There has been widespread concerns raised over the lack of progress made to date on the ambitions for the programme, which were first set out in the Building the right support strategy in 2015. A lack of high quality community services available for individuals in inpatient settings to 'step down' to is seen as a key barrier to progress. Despite these challenges, the long term plan has set a new commitment to further reduce inpatient provision for people with learning disabilities and autism – to less than half of 2015 by March 2023/24.

In our survey we sought to understand their experience of the programme to date. Trust leaders stated:

- there has been long delay in the programme and not enough progress has been made

- the programme does not have enough of a profile

- national leadership over the programme has been a concern

- the community infrastructure needed to facilitate closure of inpatient services is still not there or is being delayed.

Some developments to support the Transforming Care Programme are floundering due to lack of clarity on funding and commissioning responsibility between CCGs and specialist commissioning.

Mental health trust

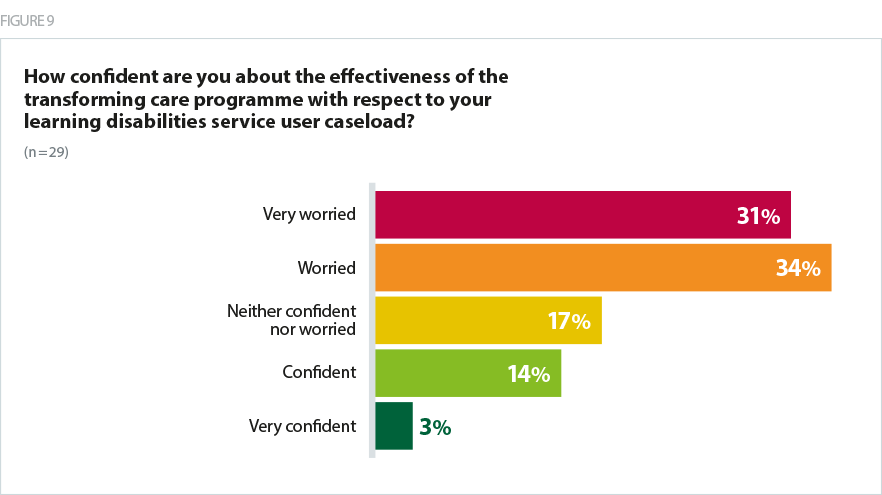

As shown in figure 9, of those trusts with services that fall within the remit of Transforming Care, 66% were worried or very worried about the effectiveness of the programme with respect to managing service user caseloads.

Simply insufficient progress. There is a risk that we are vilifying health provision and securing inadequate social care provision that then collapses

Mental health trust

Moves to system working

Our survey also provided an opportunity to better understand mental health trusts’ perspective on progress towards greater system working through STPs and ICSs. Trust leaders identified the importance of additional investment, collaborative leadership, system partners taking collective responsibility for issues around demand and capacity, and taking a population health focused approach to help improve mental health services in their local systems.

We have ensured that mental health is a mainstream part of the STP and not a separate silo dealt with outside of all the other issues.

Mental health trust

Indeed, one trust leader said that in their system there was a new collaborative approach and some non recurrent investment to develop longer term sustainable models for rehabilitation, CAMHS, eating disorder and learning disabilities services.

The single approach by the STP is excellent and we have a strong work stream. What is less good is the differing approaches locally by the four borough CCGs. This means there is a constant dialogue to ensure mental health services remain in tact and we can deliver them in a resilient way. It would help to have one commissioner.

Mental health trust

Whilst many mental health trusts have good working partnerships across systems and are positive about the direction of travel in their local area, our survey findings reveal the level of trusts’ engagement with the drive for greater system working is varied.

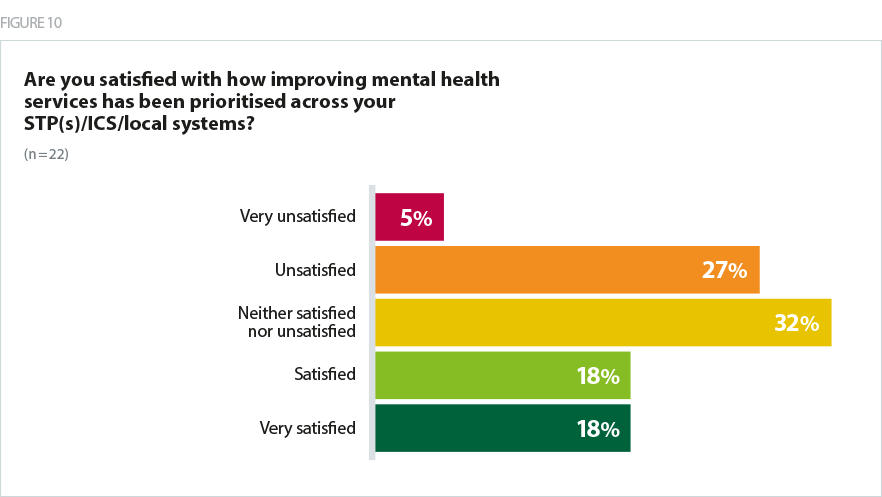

As shown in figure 10, only just over a third (36%) of trust leaders said they were satisfied or very satisfied with how mental health had been prioritised within their STP/ICS/local system and 32% said they were neither satisfied nor unsatisfied.

We also found that only 32% were confident or very confident that current system working and plans will lead to improvement in their trust’s capacity to provide timely access to mental health services to the local population. Some trust leaders feel mental health has a high enough profile in their system’s agenda and commitments have been made, but that this has not yet translated into additional investment.

It has a high enough profile on the shared agenda but has to date led to little additional investment.

Mental health trust

No new investment, lots of talk and 'commitment'.

Mental health trust

It is vital that this variation is addressed and that all mental health trusts have good levels of engagement with the NHS’ drive for greater system working. Mental healthcare provision has undergone a fundamental transformation over the past 30 years. Given the journey the sector has been on, it has much to offer in terms of learning and expertise – from implementing complex system changes to delivering more personalised care pathways – as the NHS continues on its journey to fundamentally transform how services are organised and delivered to better meet the changing needs of the population.

Mental health trusts, with their relative freedom from structural financial deficits and their strong existing relationships with primary and social care, are really well placed to spearhead integration across sensible local systems. They should be encouraged in STPs and by regulators, but rarely are!

Mental health trust

What the survey results have shown is that, if we are to address the care deficit in mental health services, there are a number of issues that must be tackled across the three key components of the operating landscape – funding, commissioning and system working:

- improved and transparent mechanisms that guarantee that mental health funding reaches frontline services provided by trusts

- expansion and roll out of mental health new care models, fostered by less fragmented commissioning and a reduction in the frequency of retendering

- greater understanding within STPs/ICSs/systems of the mental health and wellbeing needs of local populations in order to ensure mental health service delivery is prioritised accordingly

- greater engagement with mental health trusts to address variation in mental health trusts’ experiences of working within STPs/ICSs/systems

- clear expectations around delivering on national investment and initiatives for CCGs/STPs/ICSs to deliver against.

Case study 3: Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust discuss an initiative that is working with local third sector partners to deliver to support people in West Sussex with mental health needs.

Pathfinder is a new initiative that streamlines access to mental health support in West Sussex. Sussex Partnership has joined forces with ten established third sector providers in the county to ensure that people with mental health needs can find the right support. The service offers to walk alongside people to help them access the right healthcare for them. This could be primary, secondary or third sector care.

Pathfinder operates in nine areas in West Sussex. Each area has a single point of access phone number and email address to make it easy for people to be able to find all the information they need in one place. Any individual or professional living or working in West Sussex can make contact to get advice, information and signposting to available support.

By providing this single point of contact, the service hopes to help keep people well as they can signpost them quickly to where they need to be and prevent someone becoming more unwell as they try to navigate services without support.

Pathfinder is:

- an alliance of local mental health support organisations

- different services working together to give advice, information and support

- for people with mental health problems

- for carers, family, friends and professionals.

Pathfinder offers:

- a single point of access to mental health and wellbeing support

- a range of services to support people with their mental health and wellbeing

- advice, information and sign-posting, including clear information about what support is available locally

- access to a clinical service provided by nurses and occupational therapists from Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust who work alongside other Pathfinder agencies.

Pathfinder values the expertise of people with lived experience of mental health challenges and actively involves them in the design, delivery and monitoring of services. The name, Pathfinder, was a suggestion from service users and the collaborative is proud to operate under this umbrella. The Pathfinder website offers further information, tips for wellbeing and information and resources.