Trusts are working as hard as they can to deliver more activity using the resources they already have. In this section we consider the main barriers to improving operational performance and productivity which have emerged since the pandemic.

Measuring productivity and the impact of the pandemic

Productivity metrics used by government, NHS England, health economists and trusts can vary in scope. However, all these measures broadly aim to capture growth in inputs (including staff, facilities, and equipment) against growth in outputs produced (including activities delivered for patients and the quality of care provided).

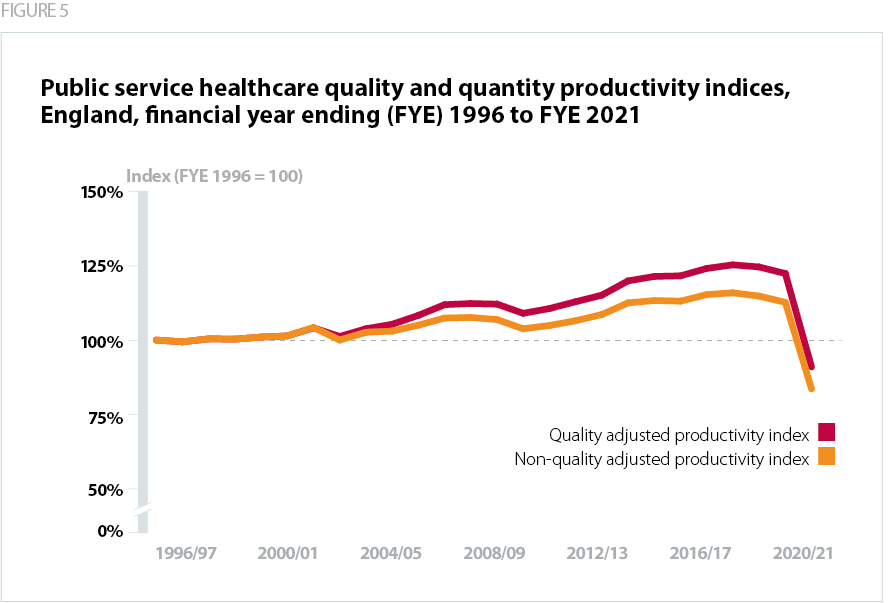

The University of York’s Centre for Health Economics compiles annual reports about NHS productivity. Prior to the pandemic its research highlighted how NHS productivity increased two and a half times in comparison to the rest of the UK economy between 2004/05-2016/17 (Castelli et al, 2019). While using different metrics, data from the Office of National Statistics tells a similar story – public service healthcare (quality adjusted) productivity increased steadily over the 2010s (ONS, 2023). Yet as The King’s Fund notes, major productivity gains since 2010/11 were achieved though wage restraint and limiting growth in staffing costs (Maguire, 2019).

Recently published research from the Centre for Health Economics suggests that NHS productivity fell by 23% between 2019/20 and 2020/21 (Arabadzhyan, 2023). This was not just due to major operational disruptions to elective and emergency care, but also because of limits to the scope of productivity measurements (Arabadzhyan, 2023). These calculations did not fully capture providers’ need to minimise the risk of Covid-19 infections by limiting elective activity, nor did they highlight the efforts of NHS staff to deliver a comprehensive vaccination programme, or to operationalise test and trace (Castelli, 2023).

What is the current productivity challenge?

As per the conditions of the spending review settlement, and the expectations set out in the government’s 2023 mandate to NHS England, the NHS is tasked to ‘improve productivity back towards pre-pandemic levels', eliminate waste (by delivering an annual efficiency target of 2.2%) and reduce unwarranted variation (DHSC, 2023). The NHS is spending more money and employing more staff, yet across nearly every care setting (except primary care), providers are struggling to improve activity levels.

As recent analysis from the Financial Times shows, even after adjusting for staff sickness and absence, the NHS currently has 11% more nurses, 16% more junior doctors, and 11% more consultants than before the pandemic began (Neville & Cocco, 2023). Yet, while trusts are delivering impressive activity gains in some categories, the NHS carried out fewer outpatient admissions and emergency admissions in March 2023 against the equivalent period in 2019 (Neville & Cocco, 2023).

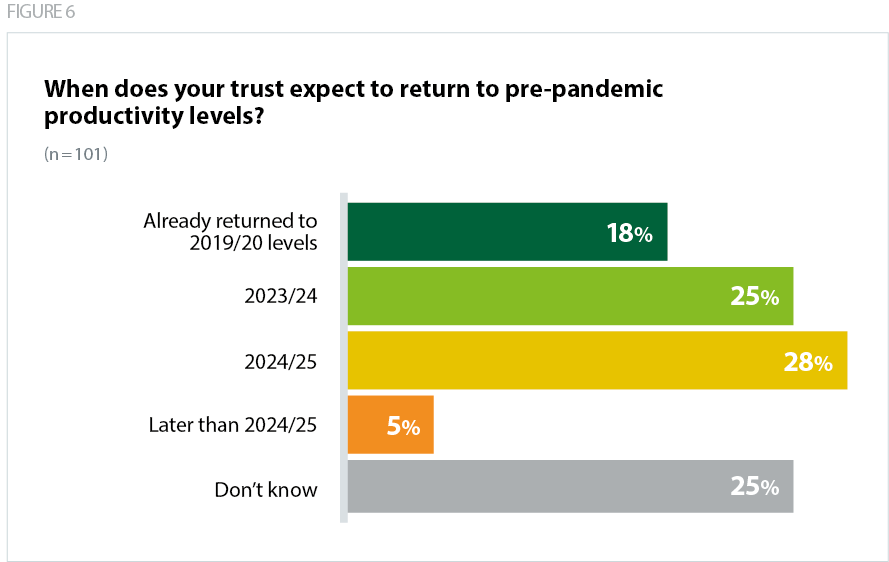

As our survey results suggest, nearly a fifth of trusts have already returned to pre-pandemic productivity levels, and over half expect to return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2024/25 in addition to making impressive performance gains in certain areas as set out in the previous section. However, despite providers continuing to drive up activity levels, productivity is below pre-pandemic levels.

As we explore below, the obstacles to improving productivity are multifaceted and vary across systems. There is also not a definitive view of the size of the productivity gap.

What are the constraints limiting trusts' ability to return to pre-pandemic levels of productivity?

In this section we cover the main barriers trusts are facing as they seek to recover operational performance and productivity.

Staff sickness, burnout and low morale

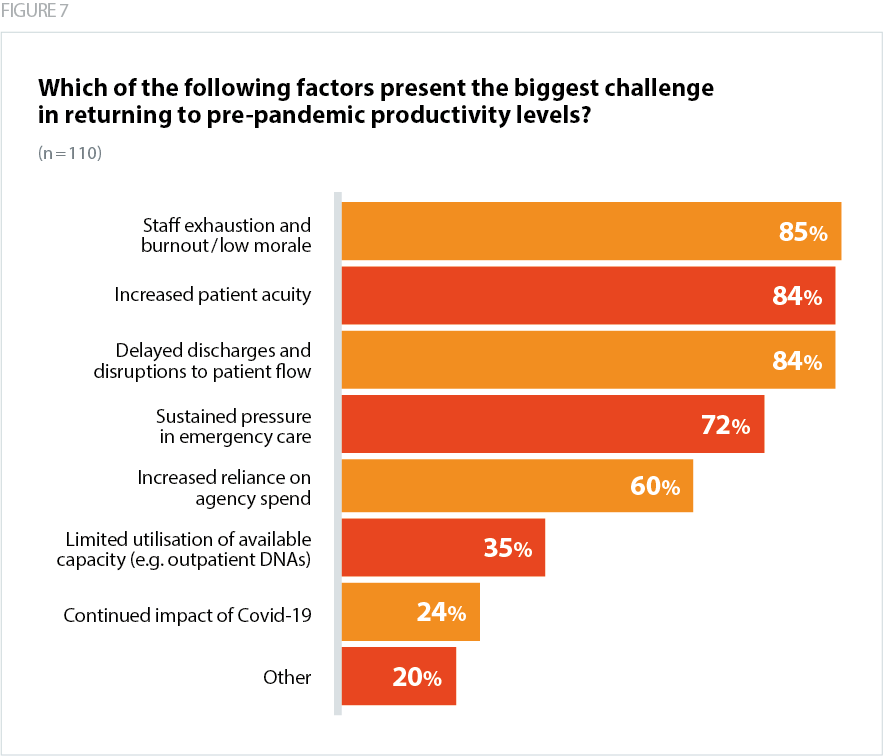

Trust leaders report that one of the biggest and most concerning challenges is staff exhaustion, burnout and low morale. This is borne out by the recent NHS staff survey which shows that all measures relating to burnout have remained persistently high. For example, just under half of staff (46%) often or always feel worn out at the end of their shift, and 34% of staff feel burnt out because of their work (Survey Coordination Centre, 2023). Almost half of ambulance staff reported feeling burnt out due to their work (49%).

Relentless operational pressures also have an adverse impact on discretionary effort from staff. It is difficult to quantify this in relation to productivity growth. However, government and national bodies must be cognisant of the material impact of burnout on individual wellbeing and on the capacity of the service to recover performance and productivity to pre-pandemic levels. For example, some staff are, understandably, now less willing to work unpaid overtime, or to take on additional paid shifts.

While trust leaders recognise the need to work with their staff to increase activity, there is a limit to what can be appropriately achieved while burnout and vacancy rates remain so high and in a context of sustained operational pressure.

Workforce pressures are increasing agency spend

Workforce pressures have a double-pronged impact on productivity growth. Limited staff availability (due to either sickness, absence, or lack of available staff across the system) leads to increased agency spend and can constrain activity growth.

The NHS continues to have persistently high levels of staff vacancies – currently sitting at 112,000. Although there has been an increase in the overall workforce, it is important to note this growth has not kept up with service demand – the vacancy rate across England in the final quarter of 2022/23 was 27% higher than the same period immediately before the pandemic began (NHS Digital, 2023d). In addition we know that record numbers of experienced staff are leaving the service or retiring early, changing the shape of the workforce and reducing the number of experienced staff available to supervise, support and develop newer recruits (GMC, 2022).

Service demand and workforce pressures, as well as the need to meet minimum staffing and safety requirements, mean trusts are often forced to turn to expensive agencies to cover workforce gaps in the short term. Trusts note the need to purchase additional (and expensive) insourcing and outsourcing capacity given operational pressures, and the need to meet national performance targets.

Trusts have also flagged that the need to resource escalation beds means their staff base can be spread too thinly, driving down operational efficiencies as well as driving up agency spend.

Lack of social care capacity

Trust leaders have made it clear that one the biggest barriers to improving the timely discharge of medically fit patients is a lack of social care capacity. Although some process improvements do lie within the gift of NHS trusts – with just under 25% of patients being delayed due to discharge processes in the hospital – longer delays in hospital are split between waits for care at home (25% of patients are delayed awaiting community health services, social care or both), in care homes (18%) and for intermediate care (22%) (Schlepper et al, 2023). Delays in social care assessments, and difficulties in quickly accessing complex housing packages, are limiting trusts’ capacity to free up additional bed capacity. One trust flagged that 20% of their total inpatient beds are occupied by medically fit for discharge patients waiting for care packages.

This is a challenge for acute, community and mental health providers. There are currently significant waiting lists for autism services and treatment beds for learning disability services and delays in some areas seeking intermediate care and rehabilitation. Adults with mental health conditions are also facing delays in accessing social care packages.

Like the NHS, social care faces severe staffing shortages. There are major concerns about the lack of qualified social care nursing staff, challenges in recruiting and retaining care workers and a need for better support for unpaid carers. Constrained staffing levels in homecare and in the care home market, as well as chronic underfunding of local government services, are exacerbating these resourcing constraints.

Trust leaders also emphasised the importance of playing their part in a better quality of conversation with patients and families, to support a broader understanding about the benefits of care at home and in the community once people are medically fit to be discharged.

"The majority of our issues are caused by flow and really high numbers of medically fit patients waiting for a package of care." Acute trust

"Our biggest productivity hit has come from increased length of stay in beds and community, increased delayed discharges, meaning more resource is being utilised for people who no longer need to be in the current part of the health system." Community trust

Increased patient acuity and longer length of stay

The average length of stay (ALOS) for non-elective inpatients has increased over the course of the pandemic. The average patient spent 8.3 days in hospital compared to 7.3 days in 2019 (Cavallaro et al, 2023). For example, between 27 February to 5 March, there were an average of 19,255 patients staying in hospital longer than 21 days (NHS England, 2023f). This is 19.6% higher than the same week in 2019, immediately prior to the pandemic (NHS England, 2019).

A sustained increase in acuity is putting pressure on services, bed capacity and in some cases, increasing theatre time. As some patients accessing services are sicker than they were prior to the pandemic, presenting with later stage diseases, or living longer with multiple long-term conditions, more resources (for example a higher nursing staff to patient ratio) and staff time are needed to deliver quality care over a pathway, impacting productivity overall.

Acute trust leaders also flagged the difficulty of ramping up elective activity because of demand in emergency care. Some trusts are using significant proportions of their bed base for non-elective patients, leaving them with little capacity to significantly ramp up activity levels on elective pathways.

"Increased use of agency and overtime to cover higher sickness and vacancies, increased recruitment, training and occupational health costs, higher acuity patients requiring more resource/staff time. All of these factors reduce overall capacity to meet demand." Ambulance trust

Clinical and managerial skills shortages

A lack of available staff can present additional challenges for trusts in finding personnel with the required skill mix for certain specialities or care pathways.

While there has been an increase in the overall workforce, it is important to note this growth has not kept up with service demand, and trusts are seeing a particular shortage of key skill sets in specific areas. Trust leaders have told us that these include imaging and diagnostics (with radiographers, ultrasound, and MRI clinicians mentioned specifically), estates, IT and administrative staff, call handlers, allied health professionals (AHPs) and healthcare support workers, and nurses (across the board but particularly bands 2-4 and 6-7 and particularly in mental health, learning disability and district nursing). The Institute of Fiscal Studies also suggests than an insufficient level of managers (both senior and mid-level) might have contributed to sluggish growth in activity levels following the pandemic (Warner & Zaranko, 2022).

Emergency demand pressures and disruptions to patient flow have also increased the need for trusts to staff escalation beds. However, it is often difficult for trusts to resource this appropriately, both in terms of using staff to cover relatively unsuitable areas like corridor care, and in retaining staff who are not undertaking work they are specifically trained for.

Lack of bed capacity

We know that the NHS has fewer hospital beds per head of population than other OECD countries, and a tendency to run with very high levels of bed occupancy (Anandaciva, 2023). The UEC recovery plan rightly sets out the aim to increase bed capacity (alongside

wider investment in community provision). The delivery plan for UEC recovery provided £1bn of additional funding in 2023/24 to help trusts sustain their escalation bed capacity. However, while additional funding injections were welcomed by the sector, and will go some way to mitigating the increased financial costs of sustaining higher capacity levels, trusts remain concerned about their capacity over the medium term to open up a sufficient volume of beds to keep pace with demand.

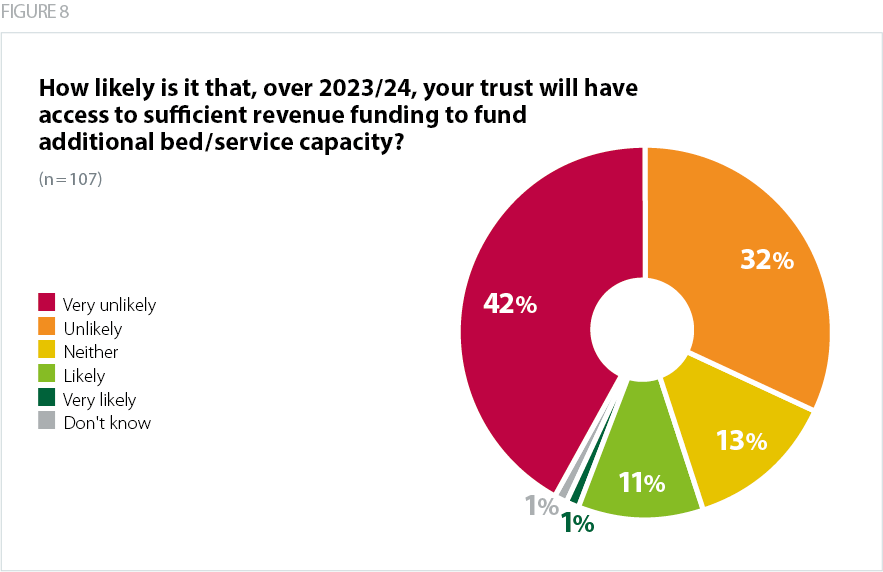

75% of trusts surveyed said it was either very unlikely or unlikely that they will have access to sufficient revenue funding to fund additional bed/service capacity or meet demand pressures while maintaining quality of care.

"The challenge is that in order to drive up elective activity we need the available beds, and with one third of our bed base taken up with patients who no longer meet the criteria to reside, and a daily bed occupancy of over 100%, this is really challenging." Acute trust

Impact of industrial action on elective recovery and strategic planning

To date, over 651,000 appointments have been postponed due to industrial action across the NHS since December 2022 (NHS England, 2023g) compounding existing pressures across the NHS and hindering efforts to recover care backlogs.

It has been vital for trusts to mitigate the risk of patient harm on strike days. Preparation for industrial action requires the highest level of sign off within organisations (as well as reporting to NHS England and ICSs). Trusts have also lost valuable leadership and managerial headspace and time for strategic planning due to the ongoing industrial action. Providers note that planning for the strikes – both in the lead up to action and managing the days of action itself – has been extremely time consuming and has heavily affected management resource, impacting on the delivery of other operational priorities. This will continue until industrial disputes are resolved.

"Real on day risk of patient harm due to lack of available resource to respond." Ambulance trust