Mental health and wellbeing have rightly risen up the NHS agenda in recent years and we are witnessing a steady and welcome change in attitudes to mental ill health. After a decade of campaigning Time to Change and Heads Together, alongside a wide range of other charities and organisations, have finally broken into the public consciousness to highlight the stigma of mental ill health and the importance of access to the right support and services in a timely way.

Politicians have also expressed their ambition to transform mental health care, create equity between the treatment of physical and mental health and enhance the priority given to mental health within the NHS. The Five year forward view for mental health and the introduction of new access standards for key mental health conditions are two key new initiatives designed to turn these ambitions into reality.

But delivering these ambitions is dependent on the quality of mental health service delivery on the ground. NHS mental health trusts are the mainstay of provision in England so analysing how well they are doing is a good way to assess whether the new ambitions we have for mental health provision are actually being delivered.

This chapter focuses on the state of the NHS mental health provider sector. We start by setting the context in the form of a snapshot of mental health provision in England and the NHS mental health provider sector’s place within it. We then analyse the state of core service provision on the ground through the results of our survey of trust leaders.

MENTAL HEALTH SECTOR SNAPSHOT

What does mental health provision in England look like and what is the case for investing in that provision? This context-setting snapshot looks at:

- current activity levels

- current level of investment

- the shape of services

- the shape of the provider sector

- the case for investing in mental health provision

- the historic structural disadvantages mental health has suffered from

- the new commitments to mental health that have recently been made.

Activity

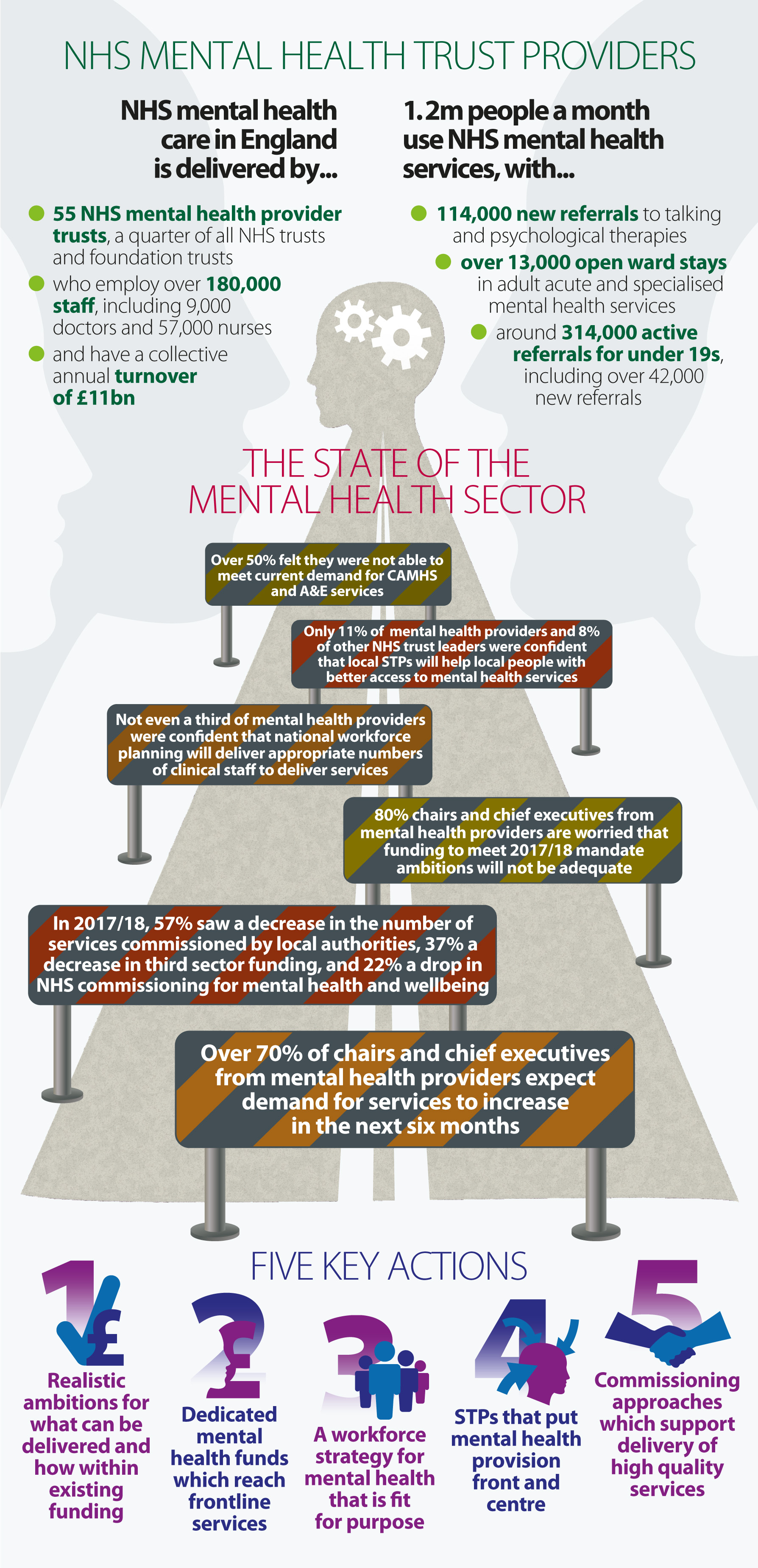

In February 2017 over 1.2 million people accessed NHS mental health services:

- 86% accessed adult mental health services

- 12% children and young people’s mental health services

- 6% accessed learning disabilities and autism services, some of whom will have also accessed adult or children’s mental health services.

These figures include:

- 114,000 new referrals to talking and psychological therapies

- over 13,000 open ward stays in adult acute and specialised services

- over 314,000 active referrals for under 19s, including 42,000 new referrals.

And, from 1 January to 31 March 2017 there were:

- nearly 3,000 referrals with suspected first episode psychosis started treatment

- 1,600 new referrals for people aged under 19 with eating disorders

- over 16,000 admissions to crisis resolution home treatment team adult wards.

Investment

In 2013/14 £9bn was spent by the NHS on mental health support and services, of which:

- £1bn was invested in children and young people

- £2.4bn in common mental health problems

- £4.8bn in severe mental illness.

The chart below, taken from the mental health taskforce report, shows how money is spent on services to treat mental health conditions and gives a good sense of both the diversity of the sector and how much is spent on those with mental health issues beyond the NHS and beyond the government.

Figure 1.0

Shape of services

Given the diversity of mental health need, NHS mental health trusts provide a complex mix of services. These can be delivered on a standalone basis or in partnership with other sectors (acute, ambulance, community trusts), other agencies (housing, police, prison services), or other organisations, in particular voluntary/social enterprises.

Care is provided across three settings:

- care provided in the community (where a service user accesses services from home, or another domestic setting, including a crisis house)

- inpatient care, usually an inpatient ward

- secure care, in a locked setting.

Services can broadly be categorised as:

- adult services (which would include services for older people, and also be subdivided for women’s services)

- children and young people’s services

- urgent and crisis care – including liaison psychiatry, work as part of the Crisis Care Concordat, initiatives such as street triage and homelessness outreach services

- forensic services, in locked settings, usually subdivided into low, medium and high secure settings.

Mental health trusts treat, and seek to prevent, a host of mental health conditions. A simplified list is set out below:

- addiction

- anxiety and depression

- dementia and memory

- eating disorders

- gender reassignment

- perinatal mental health

- personality disorders

- psychosis and schizophrenia

- sexual problems

- traumatic stress.

Shape of providers

There are 55 NHS mental health trusts focusing predominantly on delivering mental health services, and a further 20 which deliver combined mental health and community services.

Although NHS mental health trusts make up the largest single type, there are other providers:

- over 80 independent providers of mental health inpatient services

- over 100 independent and social care organisations providing community-based mental health care and/or learning disability services.

The market value for mental health hospital services (as opposed to wider community mental health services) was £4.3bn in 2014/15, with the independent sector responsible for £1.3bn of this revenue, a 29% market share. NHS mental health trusts have a collective annual turnover, across all types of mental health provision, of £11bn and they make up a quarter (24%) of the NHS provider sector by number of providers.

The economic case for investment in mental health

There is a strong economic case for investment in mental health services, as a number of studies clearly demonstrate. Work by the London School of Economics and the Centre for Mental Health calculated the economic and social costs of mental health problems in England in 2009/10 at £105.bn; with indirect costs due to unemployment, absenteeism and presentee-ism at £30bn, compared to a direct health and social care cost of intervening of £21bn and a human cost of £53.6bn.

Looking at more specific, but relatively common, conditions such as psychosis, a 2014 study has shown that intervening early in psychosis can mean that, over 10 years, for every £1 invested a possible £15 cost can be avoided. At a time of financial constraint these arguments are compelling, although the length of time for the return could be regarded as a challenge. This economic case was also clearly brought out in the NHS Five year forward view, with its focus on employability and helping people with enduring mental health conditions gain or stay in employment.

Structural disadvantages

Mental health provision and NHS mental health trusts have suffered an historical, structural disadvantage compared to physical health provision and other NHS trusts such as acute hospitals trusts, for a number of reasons:

- stigma - the stigma associated with mental health in society, reflected politically and institutionally, has meant that only a significant minority of those in need seek help at all or at the right time, meaning that provision of services has not been a priority for the NHS as a whole

- funding and payment systems - alongside the need to boost funding overall, the sustained use of block contracts has not resourced providers sufficiently for escalating demand or enabled wider service investment. Although this is changing through the introduction of different payment systems, it is a significant legacy issue

- commissioning - following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act the commissioning of mental health care by local and national commissioners has been fractured, impacting on the efficiency and continuity of care. On top of that, a number of those wider services supporting mental health service users, such as substance misuse or public health more generally, are now commissioned by local authorities. This has introduced delays and inefficiencies into the coordination of care and has meant that investment in those services has decreased as financial pressures on local authorities have risen.

New commitment

The Five year forward view for mental health implementation plan sets out how the welcome new commitment to transforming mental health services should be delivered. The key elements of the plan focus on:

- children and young people’s mental health

- perinatal mental health

- adult mental health – common problems; community, acute and crisis care; secure care

- health and justice

- suicide prevention

- sustaining transformation with new models of care; a healthy NHS workforce

- infrastructure

- support from the centre.

The NHS mandate sets out two key provisions:

- 24/7 access to mental health crisis care in both community and A&E settings

- People with mental health problems should receive better quality care at all times, accessing the right support and treatment throughout all stages of life…This will require great strides in improving care and outcomes through prevention, early intervention and improved access to integrated services to ensure physical health needs are addressed too…To close the health gap for people of all ages, we want to see a system-wide focus on prevention and early intervention, as well as improvements to perinatal mental health. Central to this approach…the delivery of, the Five year forward view implementation plan. Overall there should be measurable progress towards the parity of esteem for mental health enshrined in the NHS Constitution, particularly for those in vulnerable situations.

THE SURVEY – WHAT THE MENTAL HEALTH FRONTLINE IS TELLING US

While there are signs that the new commitment to increase support for specific mental health services is starting to bear fruit, it is important to judge the quality of mental health service provision in the round.

Our survey reveals a concerning picture of core NHS mental health service delivery on the ground in seven key areas, each of which is set out in more detail below:

- demand for service is rising rapidly

- the extra financial investment is not running the NHS mental health frontline

- workforce challenges are increasing

- taken together, these are impacting adversely on access to and quality of service delivery

- commissioning is fractured

- support between different parts of the NHS, as embodied by liaison psychiatry, still needs to be improved

- the new sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs) are not giving sufficient priority to improving mental health provision.

Demand for services is rising

Demand for mental health services is rising at a rate that matches and in many cases exceeds that experienced by the acute sector. This is the case for services for adults, and children and young people. Bed occupancy rates for inpatient units are regularly exceeding 100% in many trusts, which, as well as leading to a negative experience for service users, also creates consequential pressures on emergency services provided by acute and ambulance trusts.

Particularly concerning is the growth in children attending A&E departments for psychiatric reasons and the growth for referrals in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) which have increased nationally by 44% over the last three years.

This reported growth in demand is reflected in our survey. The majority of mental health trusts leaders - over 70% - expect demand for health services to ‘increase’ or ‘substantially increase’.

Figure 1.1

As figure 1.1 shows, mental health trust leaders expected demand increases across all seven areas listed - the key mental health delivery areas: CAMHS, talking therapies, crisis care, elderly care, early intervention, inpatient care and perinatal mental health.

Particularly concerning is the fact that 90% expected an increase in demand for crisis care, and that the two areas where trusts were anticipating a ‘substantial increase’ were CAMHS and access to psychological therapies (such as CBT or talking therapies). The demand increases in these fields are not matched by an increase in the available workforce or by commissioning or funding intentions.

A trust leader gave this insight: "We deliver CAMHS...We need universal coverage of intensive home treatment teams way more than we need more inpatient beds." Another said: "Demand is rising as the other safety nets [are] removed as a result of local government cuts."

The survey shows two key underlying reasons for increases in demand. First is the growing public focus on mental health which is uncovering unmet demand. Campaigns such as Time to Change and Heads Together, which seek to tackle the stigma surrounding mental health and encourage people to treatment, are somewhat understandably leading to a higher demand for services. Second are broader societal pressures – such as societal expectations, workplace pressures and the overall pressures of a faster pace of life – leading to a greater need for mental health support. This is particularly noticeable among children and young people.

As one trust leader put it: "The increased attention being paid to mental health requirements, quite rightly, will probably lead to more people being willing to seek care." Another commented: "More people of all ages are becoming ill as a result of the pressures of modern life."

However, although the numbers are very small at the moment, there is some levelling out or decreases in demand for inpatient care and early intervention. This could be the start of the recently introduced access standards for mental health making an impact, and the changing shape of mental health provision, moving care from inpatient to community settings. One trust leader commented: "[Our decrease in inpatients [is] due to transformation and strengthening of community services."

Importantly the overall rise in demand is not only being experienced by mental health trusts. Leaders from other trusts - hospital, community, and ambulance - echo this position. Two-thirds had seen an increase in demand for mental health services for patients in their trusts, with none seeing any decrease, as figure 1.2 demonstrates. The impact of the rise in demand for mental health services is felt across the whole system.

Figure 1.2

Financial investment is not reaching the NHS mental health frontline

The publication of the Five year forward view for mental health and its delivery plan set out the scale of collective ambition for mental health provision. These have been translated into a set of provisions in the NHS Mandate. The additional funding to support delivery of the Five year forward view for mental health is £1.4bn over five years and for the Future in Mind programme (for CAMHS) it is £1.25bn. There is early evidence that the overall level of money spent in mental health in the NHS is rising, as intended.

NHS Providers understands that last year mental health services saw a total increase of more than 7% nationally. However, NHS mental health trusts received on average only 1%. A mixed economy in services – across third sector and independent organisations – is part of the current model of provision. However, the system as a whole must recognise that the majority of transformation initiatives, management of urgent and emergency care pathways, whole population healthcare approaches, are driven by NHS mental health trusts. They need support to maintain these core services.

Is this extra funding reaching the NHS mental health trust frontline, where the majority of key mental health support is delivered? As figure 1.3 shows, 80% of mental health trust leaders were not confident that the overall investment for the ambitions in the NHS Mandate was adequate or that it would reach the frontline.

Figure 1.3

There are number of reasons for funding failing to meet the NHS mental health frontline and keep up with rising demand.

The new funding for mental health has not been ring-fenced. Trust leaders highlight that earmarked mental health funds are used for other priorities, compensating for wider pressures in the system, such as population and inflationary pressures. Respondent comments included: “The money is not passed on, it is used to bail out the CCGs and the acute sector”; and “No investment at all to deliver transformed services. Real terms disinvestment with some CCGs investing significantly less than their growth”.

Where new mental health funding is flowing, it is either being targeted at new services or is allocated to non-NHS mental health trusts. This does nothing to alleviate the growing pressure on core services, many of which are facing significant demand increases.

Many providers are experiencing significant pressures as a result of cuts in local authority and social care funding. These have increased demand for both adult and children’s services, with higher numbers presenting at secondary services who would usually have been supported by local authority funded third sector services, and also increases in delayed transfers of care due to a lack of community support services. As one trust leader indicated: “Extra mental health spend is not going into mental health five year forward view standards due to growth in Section 117 packages of care post discharge”.

NHS mental health trusts are still paid largely via block contracts which do not take account of rising demand, and have been asked over each of the last five to seven years to realise significant annual cost improvement programme (CIP) savings of 3-6%. This has had a major impact on the provision of the core services, particularly since the National Audit Office (NAO) pointed out that the costs of improving mental health services may be higher than current estimates.

There is a lack of transparency in how mental health funding allocated from clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to mental health trusts is accounted for. This makes it difficult to track which of the following reasons is responsible:

- funding not reaching the CCG

- funding reaching the CCG but not being spent on mental health

- funding being spent on mental health but not in the NHS mental health provider sector

- funding being spent on the NHS mental health provider sector but on new as opposed to core services

- funding being spent on core services, but spend not keeping up with demand increases.

There have been welcome moves to increase transparency, driven by the NHS England mental health director and her team, but more is needed here.

These concerns about the failure of increased mental health investment to reach the NHS mental health frontline are shared across the wider NHS provider sector. As figure 1.4 shows, only one in five leaders from other (non-mental health) provider trusts thought that increased investment would change access to mental health services for their patients, with nearly two-thirds believing access would stay the same or decrease. However even those expressing confidence also express a degree of caution: “hopefully. But we’ll see how it gets delivered in practice”.

Figure 1.4

Workforce challenges are growing

Having the right workforce, with the right skills in the right place, is central to meeting the shared ambition to improve mental health service provision on the ground. Our survey shows that NHS providers are struggling to find enough staff to deliver existing services to the right quality let alone being able to find new staff to extend services to new users or create new services. These issues must be tackled speedily. Given the lag to recruit and train staff, there is an argument that the timescale for delivering the new ambition now looks far too optimistic. The lack of staff in specific roles in some specialties, coupled with rising demand in these areas, is causing particular concern.

Health Education England has indicated that at least an additional 19,000 staff are needed by 2020/21 to deliver the mental health ambitions set out in the Five year forward view for mental health. Their national level strategy for delivery is only now emerging, with a huge amount to be done locally to ensure effective delivery.

Across the mental health sector, levels of confidence in national workforce planning are low. As figure 1.5 shows, no more than a third of respondents overall were confident that national strategic workforce planning will deliver appropriate numbers of staff to meet mental health targets.

Figure 1.5

One trust leader summed up the approach being taken in their area: “Local solutions are being developed as the national workforce plans are not sufficient in most areas”.

Figure 1.1 outlined the areas where demand for services is rising, including talking therapies, crisis care and CAMHS. Matching that data to the areas of concern in terms of workforce supply, paints a particularly challenging picture for both crisis care and CAMHS where 46% and 50% of mental health trust leaders are 'worried' or 'very worried' that the right numbers of staff will be delivered. Only for talking therapies is the picture marginally improved, with 46% neutral on the issue and 18% 'confident' or 'very confident'.

Other issues also need to be taken into account that impact on mental health workforce supply:

- changes to nursing bursaries - it is not yet clear what impact the change to bursaries will have on the ability of the mental health sector to attract new enrolments. However the profile of the mental health workforce is more mature and better educated (in terms of first degrees) than the general NHS workforce, and it is possible that the loss of financial support could have a particularly adverse impact, although we are awaiting firm data here

- attrition rates - the mental health student cohort experiences higher attrition rates (ie the conversion from training place to staff member) than the general NHS workforce which will further reduce the actual numbers in the workforce compared to projections

- training placements - without a published strategy from Health Education England on the delivery of the workforce in mental health on which funding allocations from other national bodies will be based, it is unclear how training placements will be made available to NHS mental health providers

- lack of funding certainty – NHS mental health trusts require certainty of recurrent funding increases if they are to commit to increase their permanent workforce. As already illustrated, extra mental health funding is not currently flowing to the NHS mental health trust frontline as intended/anticipated. This makes it much less likely NHS mental health trusts will commit to the planned and desired increase in their permanent workforce.

A key and enduring challenge for all providers and for the quality of mental health services overall is staff health and wellbeing. Recent research by Royal College of Physicians is highlighting burnout as an increasingly significant problem. This will have a knock-on effect on quality of care and increased risk of harm. A total of 41% of staff from mental health and learning disability trusts reported feeling unwell due to work related stress in previous 12 months. Only staff from ambulance trusts reported higher rates.

Impact on access to and quality of services

Rising levels of demand and the lack of financial and staff resources to manage them adversely impacts both access to and the quality of frontline services. Resourcing pressures are resulting in higher thresholds for referrals into secondary services from GPs, and there is also a direct correlation between timely treatment and outcomes, particularly for conditions such as psychosis or those related to drug and alcohol misuse.

Our survey showed concern at trusts’ ability to meet demand across the range of services. Although two-thirds of trust leaders believe they are managing demand for perinatal, elderly care specialist support and police and crime services, this drops to less than half managing demand for CAMHS and A&E services (see figure 1.6). These figures are particularly concerning when one compares these levels of access to what might be regarded as access to similar services in physical health:

- 92% of patients receiving elective surgery with 18 weeks of referral

- 85% of cancer patients being seen within 62 days of GP referral.

Figure 1.6

As figure 1.6 shows, only a little over 10% of respondents felt their trusts were both managing demand and planning for unmet need. Taken together with other evidence, these results paint a concerning picture for the future quality of mental health services:

- responsiveness – the survey shows a worrying inability to respond as effectively as desired in a crisis situation; a worrying inability to meet spiralling demand in CAMHS which will impact on future demand for mental health services; and a worrying inability in the vast majority of trusts to make inroads into those needing, but not yet receiving, services

- right capacity in the right place - a resourcing shortfall is leading to local bed capacity shortage, which is pushing up out of area placements in both CAMHS and adult inpatient care, as well as driving inappropriately early discharges. This can mean unnecessary re-admissions or the same service user re-presenting for support at a later date. Work by NHS Benchmarking, and a review of provision of acute inpatient psychiatric care pointed out that, in aggregate, there are enough inpatient beds in CAMHS and adult services, but they are not in the right place to meet local demand

- older people’s mental health – currently, older people’s mental health needs are too often inappropriately co-located with dementia care despite the needs, and treatment/support required, being very different. Given demographic trends, this is a major concern which will put additional strain on services as providers see increasing numbers of frail elderly people with severe mental health needs, where the appropriate facilities are not available

- community provision - the decommissioning of community support services funded locally by both CCGs and councils adds to the capacity issues trusts face, as patients and service users are trapped in the expensive end of the specialist pathway, as there is nowhere else to provide treatment. Alongside this, the NAO has raised concerns about community provision, and its ability to meet the needs of service users, following the Transforming Care for Learning Disabilities committed CCGs to repatriating LD service users into community settings rather than receiving inpatient care.

Fractured commissioning

The impact of commissioning structures and decisions on managing demand, financial investment and both access to and quality of services emerges strongly in the survey.

The fractured nature of commissioning in mental health – split between NHS England for specialist commissioning, local CCGs and councils – too often leads to an uncoordinated care pathway. This is less efficient, with patients often treated in expensive, inappropriate care, or it means that patients are unable to access a service at all.

However the most direct consequence of the changes to commissioning since 2012 is financial. Mental health services are commissioned by CCGs, NHS England, council public health functions, other council functions and the third sector. Across all of these groups mental health trusts saw a decrease in the levels of services commissioned for 2017/18 compared to 2016/17 (figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7

The most notable change is in the area of council commissioning of all types, where no trusts saw an increase on the previous year, 59% saw a decrease in public health commissioning, and 56% saw a decrease in other types of council commissioning. Also, given that councils are often the main financial supporters of third sector organisations it is not surprising that 37% of trusts believed that commissions from this source had decreased this year, against 30% last year.

Financial pressures on councils mean that mental health trusts are in a position where services are decommissioned altogether or severely restricted. This leaves them to either fill the gap directly by providing services themselves, without payment, or needing to provide much more expensive treatment for service users, who present much later.

Trust leaders reported the impact this is having:

"Decrease in local authority funding has led to a reduced service"

"Services are under significant pressure particularly in patient and home treatment but this is knocking on to other services"

"The impact is increasing levels of unmet need and increasing pressure on our staff trying to deliver increased demand on less resources"

Inadequate priority for mental health in STPs

Over the past 30 years the mental health sector has demonstrated its ability to deliver significant transformation - moving services out from asylums into the community, creating bespoke mental health trusts and designing and delivering more patient-centred care pathways. This experience and learning means the sector has much to contribute to the current NHS transformation agenda.

The NHS as a whole is seeking to transform. It is using STPs - a key part of the new NHS landscape - to lead the transformation process. If mental health services are to flourish and we are to realise our new ambitions, it is vital that mental health is at the centre of the STP process. A recent report by The King's Fund and the Royal College of Psychiatrists on mental health services in the new care model vanguards, which are now part of STP delivery, throws important light on to the extent to which these test beds are working to the benefit of patients and service users in mental health. The report does not paint a positive picture. The mental health offer is often not core to enhanced service models and too often they are under-using the beneficial contribution that mental health professionals can make.

This is echoed by our survey which asked how confident respondents were that STPs would improve timely access for local populations to mental health services. There are 44 STPs across the country. Feedback from mental health trust leaders strongly suggests that mental health services are not sitting centrally in these planning processes with only 11% confident that their local STP will lead to improvements in access and quality of services. (see figure 1.8). Over 40% were 'worried' or 'very worried', and 45% were neutral on the issue.

Figure 1.8

Two themes emerge from trust leaders’ feedback:

- acute focus - the STP is focusing on acute services, or mental health is not sitting in the mainstream of the STP’s plan, process and thinking: “too acute focused”, “All the focus and STF funding has gone to the acute trusts. The mental health investment letter remains unsigned” “….in the other [area] it is yet to be mainstreamed in the way I would wish”

- lack of investment - the STP is not or is no longer investing in plans for mental health provision. “While our submission in November led to increased investment planned for mental health, CCGs locally now wish to change this as they report they can no longer afford the commitment in the plan. The commitments in the plan were not evidenced in contracts for 2017/19”, “The mental health component of the STP was very good and would support delivery of improved services however the required investment is no longer available”.

Interestingly the perspective from other trusts - acute, community and ambulance - on mental health involvement is even less positive. As figure 1.9 shows, only 8% were confident that STPs would deliver improvements and 46% were 'worried' or 'very worried' about the role of mental health. They commented: “mental health has not been an issue to date” and “priority is acute, primary care and urgent care”.

Figure 1.9

More needed to improve working across NHS sectors: liaison psychiatry

Effective liaison between mental health and other NHS services, particularly acute care is vital. The survey therefore looked in detail at liaison psychiatry as an example of an important cross-sector service. Liaison psychiatry features heavily in the Five year forward view for mental health, and the aim is for 50% of all trusts to have in place 24/7 all-age liaison psychiatry services by 2020/21. We wanted to use the survey to test what progress was being made to meet these ambitions.

As the data in figure 1.10 shows, the most prevalent provision of 24/7 liaison psychiatry is for urgent care in A&E and for police and crime services, at 76% and 61% respectively (84% and 69% if including those planning to introduce from 2018/19). For CAMHS this drops to 62%, and currently only 35% of trusts deliver 24/7 perinatal liaison psychiatry.

Figure 1.10

The responses to the survey in this area once again bring the impact of commissioning decisions on provision to the fore. One trust leader commented: “Though we are not the CAMHS provider….commissioners have not ensured appropriate services for under 25s and we cover the gap.” Another said: “The 24/7 liaison service was decommissioned by CCGs a few years ago. There is an extended daytime liaison service, crisis team and CAMHS on call at night but not a comprehensive 24/7 service.”

For acute trusts, the picture is less clear, as figure 1.11 sets out. Although over half have 24/7 liaison services in place or due to be introduced in the next year for urgent care, and just over a third had them for inpatient care, they commented that even when it was technically in place delivery could be “patchy” particularly at evenings or weekends. Over one in four did not have 24/7 liaison services in place at all for inpatient care, and one in five for urgent care.

Figure 1.11

This comment from a trust leader shows how resourcing is impacting on delivery plans: “Currently plans [are] being worked up to develop liaison service but will be dependent on funding being released from other services to fund this”.

It is worth noting that liaison psychiatry is one of the areas of service provision subject to the new access standards for mental health services, introduced to improve quality and access. Mental health trusts are working hard to meet these new standards but the picture is mixed. Figures 1.7 and 1.8 show the picture for liaison psychiatry, where 24/7 liaison psychiatry is a minimum requirement. The standard for talking therapies is being met in aggregate but drilling down to local figures shows that 83 out of 211 CCGs had not achieved the required standard. Although crisis care has improved dramatically through the Crisis Care Concordat, crisis mental health services are still struggling to meet demand. Yet again the message is consistent – timely access to and the right quality of core services can only be achieved through effective resourcing and commissioning.

WHAT PROVIDERS NEED

Our survey sets challenges to frontline core mental health service delivery, which, despite some progress with the mental health access standards, stand in the way of realising the shared new ambition to transform mental health services.

Providers need:

- realism about demand and what’s needed to meet it, recognising that increased focus on mental health and current societal pressures will generate more demand

- better ways to guarantee that mental health funding reaches the NHS mental health trust frontline

- a robust workforce strategy and, critically, support at local level to make it happen. We need to ensure that we match the ambition to expand services with a realistic view of how quickly we can grow the workforce to deliver this

- STPs to give enhanced mental health service delivery greater priority in their plans, processes and thinking

- commissioning to be overhauled to support the delivery of more coherent care and to maintain the level of financial investment in both core and new priority mental health services.

Support for mental health services at the most senior level is very important. It keeps mental health challenges on the agenda but real change will come about through local action and engagement. It is critical that there is a central/local dialogue to:

- maintain transparent monitoring and reporting of what is actually happening on the frontline, involving local providers to provide a true picture

- ensure a balance between maintaining core services and extending new services

- reach a shared understanding that this the start of a long journey.

The new commitment to improve the quality and breadth of mental health provision is welcome. But it also needs to be sustained, with the current level of energy and vigour, over the long term.