A health bill fit for the future

2 July 2025

This briefing sets out considerations for the civil servants and lawyers working on the new health bill and for legislators in the commons and the lords.

Governance

The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care’s commitment to cut bureaucracy and make cost savings by abolishing NHS England (NHSE) requires changes to primary legislation. A new health bill is expected to be drafted imminently.

This briefing sets out considerations for the civil servants and lawyers working on the new bill and for legislators in the Commons and the Lords.

It draws on insight from NHS Providers’ significant policy experience within health legislation since 2011, extensive engagement with those working on the 2022 Act, and knowledge of what is most likely to enable the NHS trusts and foundation trusts delivering healthcare in England to succeed in delivering the best care for patients.

The purpose of this briefing is to raise awareness of some of the challenges that health legislation will need to address to ensure the new statutory framework supports the NHS now and into the future.

It covers why getting the legal foundations right matters, sets out key issues for legislators and those drafting the bill (focused on reallocating NHSE’s functions, ensuring appropriate checks and balances on ministerial powers, and reconciling proper oversight with the operational autonomy of NHS organisations), and makes the case that legislation is likely to be more effective if those who will be required to enact it are involved in its design.

Executive summary

The 10-year health plan will need an enabling statutory framework and operating model: a restructured NHS will need the right functions, accountabilities and incentives, underpinned by legislation.

Legislative reform must support the new operating model and NHS architecture to enable sustainable improvement and create an NHS fit for the future. The legal framework should enable, not impede, the government’s ‘three shifts’.

This is an opportunity for form to follow function, as well as recognising the crucial positive interaction between legislation and strategy. A plan without a clear, robust framework beneath it is like a train running on a broken track. The risk of derailment is significant.

Legislation, given the decision to abolish NHSE, must clearly reallocate functions (powers and duties) and aligned accountabilities, responsibilities and liabilities.

It must be readily implementable, internally consistent, and there must be effective and proportionate direction and oversight, with clarity about who is responsible to whom for what.

There must be appropriate checks and balances on the powers of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Ministerial oversight and direction should be balanced by appropriate parliamentary scrutiny. This can help promote public accountability and patient safety, prevent the over-politicisation of the NHS, and safeguard NHS organisations’ operational autonomy. This balance, between ministerial powers and organisational autonomy, upholds the principle of subsidiarity – that decision-making authority is best placed where responsibility for outcomes is held, and as close as possible to where the activity will be undertaken to produce the intended outcomes.

Considerations for legislators

- Define the scope of the required legislation. Can a minimalist approach be taken to abolishing NHSE and transferring its functions, or is wider legal reform necessary?

- Endeavour to design the system holistically, with a good understanding of NHSE’s current purpose, functions and activity, to produce draft legislation that can be consulted on for clarity and feasibility with those charged with enacting the legislation.

- Be intentional about powers delegated to ministers and ensure adequate checks and balances on those powers.

- Consider the mechanism and frequency with which ministers can instruct the NHS to effectively run a rules-based system to guide and constrain NHS bodies, balancing NHS organisations’ operational autonomy, with ensuring appropriate oversight.

- Seek appropriate independence between those with accountability for national NHS performance and those who regulate NHS organisations.

- Consider where duties (which are mandatory) or powers (which may be used) are appropriate, and the extent to which powers should be qualified.

- Ensure clear demarcation between the functions of different parts of the system. It will be important to avoid contradictions, unmanageable complexity and ambiguity.

- Ensure it is clear which body is accountable to whom, for what, and under what circumstances. Only by defining clear responsibilities can we be clear about accountabilities.

Why getting the legal foundations right matters

There are two structural frameworks which currently underpin the NHS: its operating model and the NHS Act 2006 (as amended by subsequent acts).

Both set out the functions (responsibilities, duties and powers) and accountabilities of the different parts of the system. The system now comprises the Secretary of State and the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHSE including its regions, integrated care boards (ICBs) and provider trusts and foundation trusts, as well as a number of regulators and other public bodies that interact with NHS institutions.

The 2006 act provides the core legal basis, while the operating model – whether a single document or created by various policy documents issued by the centre – gives more detail about roles and responsibilities and how the interactions between the different parts of the system should work in practice.

The two should align: inconsistency between the law and the way the system is understood or expected to operate leads to confusion, duplication and risks legal challenge.

Legislative reform must underpin the new operating model and NHS architecture to enable sustainable improvement and create an NHS fit for the future.

The legal framework should enable, not impede, the government’s ‘three shifts’. This is an opportunity for form to follow function, as well as recognising the crucial positive interaction between legislation and strategy.

A plan without a clear, robust framework beneath it is like a train running on a broken track. The risk of derailment is significant.

The legal framework must clearly allocate functions and align accountabilities, responsibilities and liabilities. It should enable, not impede, the government’s ‘three shifts’.

DHSC, working with NHSE, is currently redesigning the operating model for the NHS, most significantly to date through the refreshed National Performance Assessment Framework and proposals to reform the role of ICBs to focus on 'strategic commissioning'[2].

As the Secretary of State Wes Streeting said when he took office, major reorganisations of complex systems like the NHS are to be avoided where possible as they cause significant distraction and waste time, effort and money[3].

Now structural reform is underway, it is imperative that this legislation and the operating model is well thought through, can endure for the medium to long-term, and puts the NHS on a sustainable, workable footing.

[2] In law, ICBs were always commissioners: their role evolved through NHSE guidance.

[3] See, for example, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care's address to IPPR - GOV.UK September 2024

Considerations for legislators and those drafting the bill

This section focuses on what needs to be considered as NHSE’s functions are merged into DHSC or allocated to other parts of the system.

Early considerations

Defining the scope of the legislation

Legislation is required to abolish NHSE. It is for government to propose and legislators to consider whether new legislation should support broader reform of the NHS.

Health law has developed iteratively, with successive acts building on the NHS Act 2006. This approach has benefits: if done well, it can enable incremental improvement while sustaining institutional memory, and for a busy government, smaller, targeted change is easier to pass through parliament than sweeping reforms.

However this approach also brings potential downsides: layered legislation risks incoherence, complexity and fragmentation, leading to a potentially contradictory framework that loses the original intent of foundational legislation.

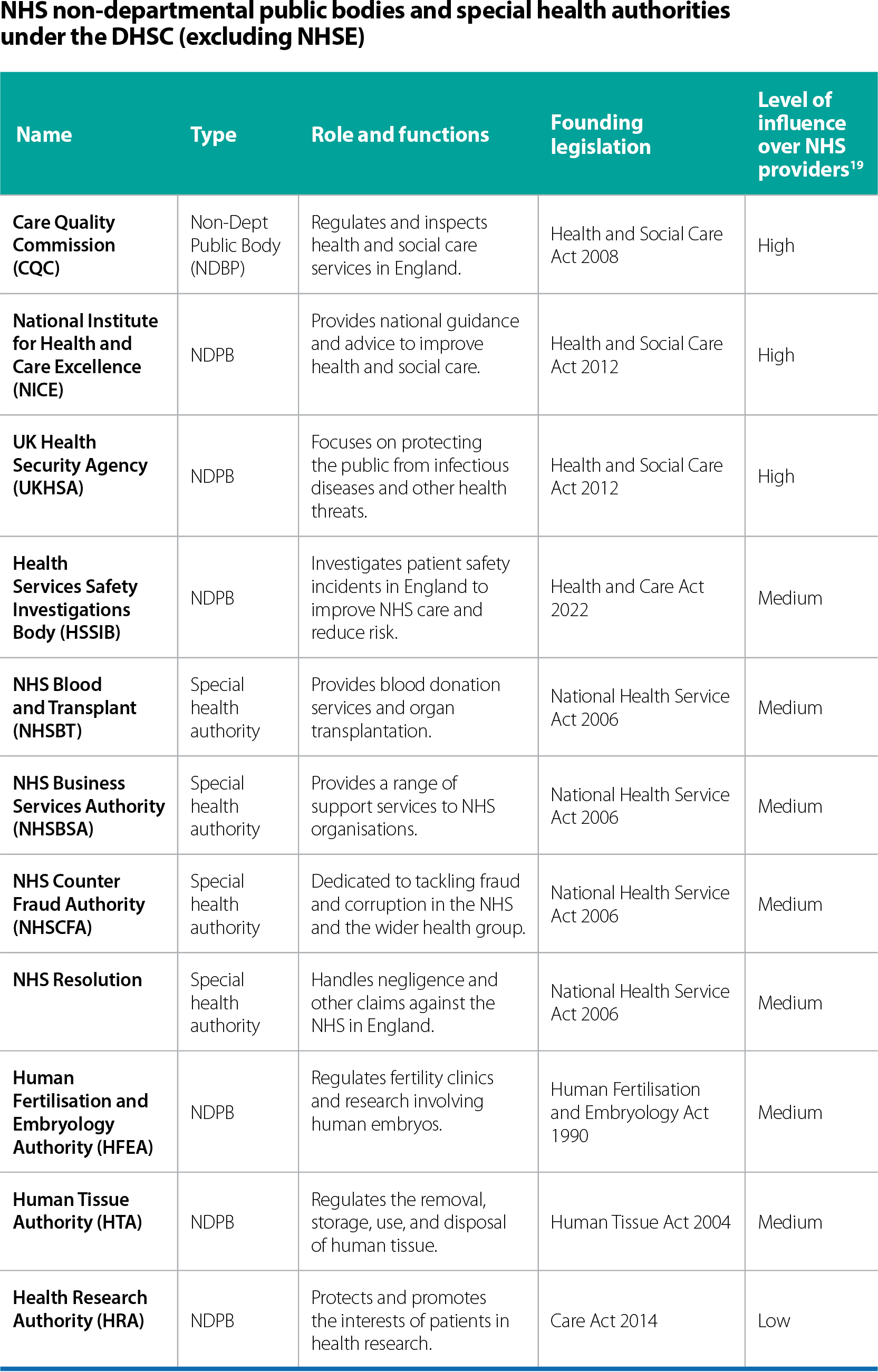

Apart from NHSE, there are other arm’s length bodies under the DHSC regulating, directing, servicing and/or advising the NHS.[4] Cutting bureaucracy and effectively redesigning the NHS system might require consideration of the functions and powers of these bodies alongside those of NHSE which need reallocation. Equally, we have stated some benefits of taking a more targeted and contained approach above.

Because the NHS is a large and complex system with many interrelated parts, it is likely that arguments will be made for broadening the scope of legislation once initial proposals come before parliament: it is helpful to consider and take advice on the scope in advance. Legislators and those drafting should also consider any consequential amendments that may be required to other legislation, for example around information governance.

- Define the scope of the required legislation. Can a minimalist approach be taken to abolishing NHSE and transferring its functions, or is wider legal reform necessary?

Taking the right amount of time and involving lawyers early

Good legislation is the cornerstone of future clarity for those asked to deliver services and make the government’s aims for the NHS a reality.

Poorly thought-through legislation can lead to:

- An inability to enact it in practice, and slow or poor implementation.

- Unintended consequences and nasty surprises (eg, window taxes[5]).

Involving lawyers early and ensuring rigorous testing and review is essential, as is a realistic timetable for the bill that enables effective parliamentary scrutiny[6]. Building in time during drafting to consider the law as it will be enacted by the people running and staffing our NHS organisations, and consulting and testing proposals with those who will enact it is essential to ensure clarity and feasibility.

- Check for clarity and feasibility with the institutions and officials that will need to enact it.

Using primary or secondary legislation, or leaving it to policy

Secondary legislation, such as regulations, can be more easily updated. There has been a trend towards using primary legislation to give ministers powers to enact secondary legislation, which can then be used for matters of policy or principle with the force of an act of parliament but without necessarily being subject to parliamentary scrutiny.[7]

We would encourage a more robust approach. Primary legislation should set out a workable architecture for the NHS, and statutory instruments (SIs) reserved for practical matters that are too detailed for an act.[8]

- Parliament should be intentional about powers it delegates to ministers.

The functions of NHS England

‘Functions’ is the broad term used to describe the associated legal responsibilities, duties and powers assigned to a body or official.

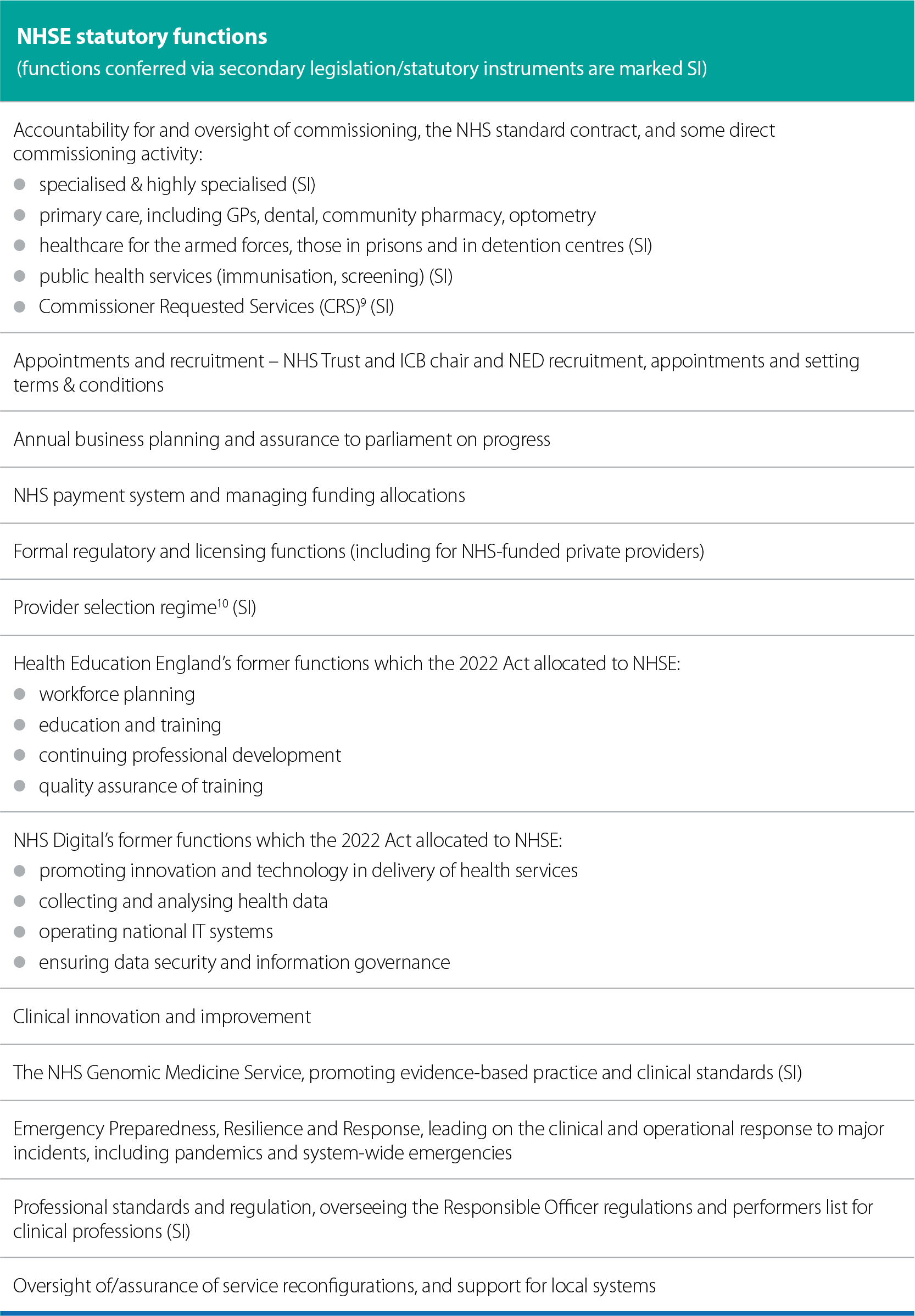

The NHS is a complex system. NHSE’s current statutory functions within that system are manifold. Abolishing NHSE and reallocating its essential functions presents a significant opportunity to undertake a systematic review of the roles and interrelationships between the different system components and evaluate where functions are best held and delivered to achieve the aims of the NHS.

Equally, there are good reasons set out above to keep the bill as simple as possible and move quickly to reallocate NHSE’s functions.

At a minimum, legislation should be internally consistent and implementable, with clear allocation of functions (powers and duties) and aligned accountabilities, responsibilities and liabilities.

- Endeavour to design the system holistically as far as possible.

Considering duties

Subsequent acts have allocated duties to the different types of organisations in the NHS. Duties are mandatory requirements: NHS bodies must act in compliance with their duties or they can face sanctions.

The 2022 act introduced the ‘duty to collaborate’ (where it will improve quality or access for patients) for trusts, for example.

Other duties include having regard to effects of decisions on health inequalities, and having regard to the NHS Constitution.

The general duties of the secretary of state currently differ from the general duties of NHSE. Duties which mandate how NHS bodies should behave and what they should do are powerful ways of enshrining values in the system.

Duties should be aligned and not contradict each other within the legislation.

Considering powers

Powers are usually discretionary: an organisation or officeholder may use a power it has but can choose not to. Some powers are qualified or conditional: for example, in the case of secretary of state intervention in service reconfiguration, this is only permissible if the secretary of state believes the reconfiguration proposed would have an adverse impact on service delivery.

While ministerial oversight is necessary for strategic coordination and accountability, qualifications such as this are important safeguards on overreach from the centre (see section below on the powers of the secretary of state).

However, many qualifications, such as the example above, require a subjective judgement to be made about whether the condition for use of the power has been met.

Judicial review can be used to challenge decisions made where due process is believed not to have been followed, which can include testing in court whether the qualification threshold was met.

Judicial review is a remedy of last resort and legislators may wish to consider introducing simpler, more cost-effective, swifter independent review mechanisms.

For example, the 2022 act removed a relatively simple mechanism to resolve payment disputes. Currently, providers’ ability to challenge funding decisions is limited to subsequently seeking judicial review if they were not appropriately consulted during the negotiation process.

Further considerations around the powers of the secretary of state are set out in the next section, but legislators should consider the extent of powers granted to any official or body and clearly define reasonable qualifications for the use of such powers.

This is particularly true in the context of reallocating powers currently held by NHSE to the department.

- Consider where powers (which may be used) or duties (which are mandatory) are appropriate, and the extent to which powers should be qualified.

- Consider including independent dispute mechanisms short of judicial review.

Reallocating the functions of NHSE

Ensuring different bodies are clear about their role and what they are free to make decisions about is a precondition for a successful system.

The relationships must make sense as a whole and lead to a well-governed system that balances direction and oversight with clarity about appropriate freedom to act.

Abolishing NHSE means its essential statutory functions must be allocated to other bodies or officials. In doing this, legislators should recognise that these will apply to real-life organisations with people in them trying to make sense of their role, responsibilities, powers and duties.

Good legislation is the foundation of future clarity for those asked to deliver services and of a successful NHS.

There should be clear demarcation between the functions (relevant duties and powers) of different parts of the system. Avoiding tensions or contradictions is particularly important.

This table sets out key statutory functions held by NHSE at present. It is not exhaustive but demonstrates the range of functions that may require reallocation.

[4] See Appendix 1

[5] The window tax of 1696 is perhaps the most well-known example of legislation with unintended consequences: a property-based tax based on the number of windows, it led to residents blocking them up to reduce the tax burden, harming public health and denying the government income. Why do some laws fail? | COUNSEL | The Magazine of the Bar of England and Wales January 2023

[6] Strengthening parliamentary scrutiny - POST October 2024

[9] NHS England supports commissioners in designating services that require additional protections due to their importance to local populations.

[10] And its requirement (Health Care Services (Provider Selection Regime) Regulations 2023, regulation 23) to incorporate ‘independent expert advice’ (currently the Independent Patient Choice and Procurement Panel run by NHSE).

- Ensure clear demarcation between the functions of different parts of the system. It will be important to avoid contradictions, unmanageable complexity and ambiguity.

Being clear about accountabilities

The cornerstone of an effective system of accountability is clarity about roles and responsibilities. The law should define who is accountable to whom, for what, and under what circumstance. Overlapping obligations should be avoided.

If the legal framework is a backstop in times of difficulty, it must provide clarity about which body is responsible, and therefore accountable, for what.

- Only by defining clear responsibilities can we be clear about accountabilities.

The powers of the secretary of state

Considering checks and balances on powers

When NHSE is abolished, the secretary of state might assume direct control of many new functions, including new powers that they may choose to exercise.

NHSE and some other NHS bodies held certain functions at arm’s length in order to:

- Maintain public trust that NHS organisations are run to provide the best possible healthcare, not for political gain.

- Protect clinical judgement from political interference.

- Protect the NHS from micromanagement and a ‘one size fits all’ centralised approach.

- Maintain NHS organisations’ accountability for their own performance[11].

Removing NHSE and reinstating direct accountability to parliament for the NHS reintroduces potential challenge along these lines.

Legislators will therefore want to be clear whether there are sufficient checks and balances on the legal powers of the secretary of state, ministers, and on any new powers introduced for local mayors and/or council leaders.[12]

It is of course right and proper that the secretary of state and ministers are able to direct NHS strategy and policy. But undue political interference and the perception of such interference – such as when approving and funding new hospitals or service reconfigurations, appointing local NHS directors, or giving the go ahead to mergers and acquisitions – should be avoided in decision-making and policy-making.

It is vital that the public has confidence that decisions are always being made with a focus on delivering the best possible patient care and improving population health as efficiently as possible.

When ministers or mayors can override local decisions, there is a risk that clinically appropriate or organisationally necessary changes are blocked or delayed, potentially compromising patient outcomes, delaying changes that would lead to a more efficient use of taxpayers’ money, as well as diverting resources from frontline care to making the case for change.

The legislation should not result in NHS decision making being more exposed to political pressure, or perceived as being so.

The 2022 Act has already strengthened the secretary of state’s powers of direction over the NHS.[13]

All powers of direction over NHS organisations need to be clearly defined, identifying the areas of decision-making and activity where and when the power can (and therefore cannot) be exercised.

If considering any further powers of direction over NHS organisations, legislators should carefully consider how to ensure that appropriate autonomy of NHS organisations is maintained.

For example, the secretary of state has formerly instructed NHSE annually via the mandate[14], setting out national priorities which are then translated into policy by NHSE. The 2022 Act enabled updates to be issued at any time.

Clear national direction can support a rules-based system setting out the guidelines for, and constraints on, NHS organisations, within which they can operate successfully.

Consideration will need to be given to the practical mechanism(s) that the department can use to direct the NHS, whether this needs legislating for, and if so, how often it is permissible to make changes to that national direction. Likewise, any new local government powers should be very clearly articulated.

This is not only important to safeguard operational independence, as outlined above, but also to support NHS organisations’ and systems’ ability to plan and invest, and to undertake medium to long-term planning to improve population health and reduce health inequalities.

The government has stated its intention to move to multi-year planning, and legislators may wish to consider whether this is important enough to include in a new act.

In addition, the 2022 Act strengthened the secretary of state’s powers of intervention and decision-making in ‘substantial’ health service reconfigurations, at the expense of local authority powers.

Extending these powers arguably ran counter to one of the core purposes of that act: to enable local collaborative decision-making. Legislators may wish to consider whether there is appetite to address this, particularly in the context of local government reform, but remaining mindful of the potential risks of political interference, whether national or local.

- Ensure there are adequate checks and balances on the powers of ministers.

- Consider the mechanism and frequency with which ministers can instruct the NHS to establish a rules-based system to guide and constrain NHS bodies, safeguarding NHS organisations' operational autonomy, and ensuring appropriate oversight.

Separating regulatory functions

There are some functions that it is particularly relevant to separate from others to avoid conflicts of interest, to sustain public confidence, and to ensure accountabilities can be allocated.

Regulation is weakened when the regulator is itself responsible for the performance of the services it oversees. This creates serious risks, most notably a conflict of interest that can undermine public trust in the fairness and integrity of regulatory decisions and crucially, risks subordinating quality and safety considerations to financial or operational ones.[15]

This issue was resolved under the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, as regulatory and commissioning duties were split between Monitor and NHSE.

The 2022 Act created a conflict by placing both sets of duties in NHSE.

There is a risk that this conflict could become more pronounced if all NHSE’s duties were transferred to DHSC, as DHSC would then hold powers of direction, allocate money from the public purse, be accountable for the performance of the NHS, and hold a monopoly on NHS policymaking, and then as a regulator would pass judgement on the impact.

To avoid this, legislation should clearly define how independent a regulator is, including when ministers can intervene and what options the regulator has if it lacks the funding or resources needed to do its job properly.[16]

To achieve separation of powers, an NHS regulator ought to be at least at arm’s length from the department. If the new NHS regions are to be responsible for regulation, legislators will want to consider whether it is proper for them to be part of DHSC. Parliament may not accept the prospect of DHSC marking its own homework.

- Seek appropriate independence between those with accountability for national NHS performance and those who regulate NHS organisations.

Additional considerations

Recognising interactions with other legislation

The government has a significant public reform agenda underway. Two areas in particular may impact on the NHS, and perhaps on health legislation: social care reform and English devolution.

There are benefits to alignment, where possible, between NHS and other legislative timetables, to maximise the opportunities for synergies and avoid a subsequent need to update primary legislation.

However, the benefits of a joined-up approach should be balanced against the risks of extending distraction and uncertainty in the NHS or in other parts of the public sector.

The links between health and social care, and the influence of local authorities, and local mayors, on NHS planning and oversight will in any case be important to bear in mind if the scope of the legislation extends beyond reallocating NHSE functions.

Additionally, we anticipate that the government will wish to move forward with the introduction of a single patient record, and this has profound implications in relation to the Data Protection Act 2008, the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the role of general practitioners as data controllers. While the abolition of NHSE does not require consideration of data protection legislation, the ambitions of the 10-year health plan likely will.

- Consider the implications of other reform programmes for this legislation.

Ensuring non-executive director appointments retain their independence

The independence of NHS non-executive directors (NEDs), including chairs, is both good governance practice and established through various NHS governance frameworks and regulatory expectations.[17]

Objective challenge from independent NEDs on the boards of NHS organisations is a core mechanism to instil public confidence in the NHS, and is intended to ensure decisions are taken in the public interest.

NED appointments are an area where the distinct organisational forms of NHS foundation trusts and trusts matters.

In foundation trusts, an independent council of governors has statutory responsibility for NED appointments to assure their objectivity.

In NHS trusts, appointments have to date been made by a succession of arm’s length bodies[18], with NHSE formally taking responsibility for appointments under the 2022 Act. It currently appoints NHS trust chairs and other NEDs, and sets their terms and conditions.

With NHSE’s abolition, ministers will wish to consider where these functions reside, and how to maintain their independence from government and from DHSC in particular.

For example, NHS trust chair and NED appointments might be undertaken and their independence assured by the Commissioner for Public Appointments.

- Consider means of maintaining the independence of non-executive directors.

Considering changes to the statutory form of NHS trusts and foundation trusts

It is not necessary to amend the statutory basis of trusts or foundation trusts in order to make decisions about abolishing NHSE and redistributing its functions.

However, given the secretary of state has remarked on aspirations to ‘reinvigorate the FT model’ to introduce earned autonomy for high-performing trusts and robust intervention for those underperforming, it is worth noting here since their organisational forms and functions are set out in the 2006 act (as amended).

It is notable that foundation trusts have some statutory powers at present that they are unable to exercise in practice, such as the ability to retain surpluses or borrow capital from commercial sources.

They also have additional checks and balances in place compared to NHS trusts, such as councils of governors, intended to ensure a continued focus on what is best for patients and service users.

Should all trusts be able to earn freedoms and be subject to stronger checks and balances through the government’s policy, it would be worth considering how these provisions fit with the statutory freedoms that foundation trusts continue to hold in law.

[11] Setting Up a New Arm’s-Length Body (ALB): Guidance for Departments (HTML) - GOV.UK May 2024 sets out various reasons why an arm’s length body might be more appropriate than undertaking functions within a government department

[12] In the education sector, for example, arm’s length bodies allocate funding, oversee quality, and inspect schools, while local authorities plan local education provision within the national strategic direction set by the department.

[13] Powers of direction allow the minister to issue direct instructions to an NHS body.

[14] Mandate_explained.pdf This Department of Health publication of 2014 relates to the 2014/15 mandate, however the introductory paragraphs provide a useful overview of the purpose and scope of the mandate.

[15] Accountability in the NHS: Implications of the government's reform programme - The King's Fund, June 2011

[16] The National Audit Office’s Principles of Effective Regulation May 2021

[17] Including the Code of governance for NHS provider trusts and The Insightful Provider Board. Independent NEDs are an essential part of a unitary board structure.

[18] The arm’s length Appointments Commission made NHS trust NED appointments until its abolition in 2012, when the similarly arm’s length Trust Development Agency (TDA) was established and took over the responsibility. The TDA joined the FT regulator, Monitor, to become NHS Improvement in 2016, which itself then folded into NHS England. The TDA, Monitor and NHS Improvement were only abolished by the 2022 Act.

Next steps and working with us

This briefing sets out some fundamental considerations regarding the abolition of NHSE, but we have not sought to address the myriad issues that might be relevant in new health legislation. This work will begin as soon as the implications of the 10-year health plan are clearer, and we understand more about what might specifically be required, or sought, from legislation.

Some of the potential issues for future exploration with trusts include:

- the legal underpinning of the optimal relationship between government and the health service;

- national payment systems and other incentives to embed the three shifts;

- the implications of devolution;

- rules on data sharing, information governance and service reconfiguration;

- the legal forms of trusts and foundation trusts; and

- whether legislation is required to enable new forms of accountable care organisations.

NHS Providers is keen to support the government to make health legislation as effective, clear and future proof as possible and will seek to work closely with the bill team. It is good practice to test the feasibility and clarity of draft legislation with those who will be asked to put it into practice and work within it.

We were pleased to engage regularly with the team drafting the 2022 act and drew on feedback from trusts as well as on our expertise in good NHS governance and good legislation.

Contact izzy.allen@nhsproviders.org with any comments, observations or suggestions relating to this briefing, or to arrange to speak to NHS provider organisations about the operating model or the bill.

Appendix 1